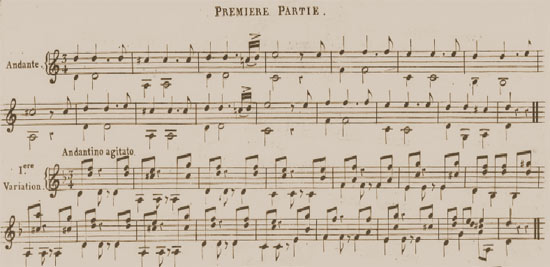

From Airs de Cour, Étienne Moulinié, Paris 1629 as early Folia on the text 'Om sijn vlam wat te vermijden' (from: Hemelschen Parnassus-bergh, 1678 Couplets de Folies variation no. 9 - Marin Marais

'Follia' variation no. 4 - Arcangelo Corelli 'Folies d'Espagne' - Raoul-Auger Feuillet including choreography (1700)

- Camerata Delft (Quirine van Hoek violin and soprano, Lotte Beukman cello, Ilil Danin recorder and virginal, Earl Christy Renaissance lute, Ricardo Rodríguez Miranda viola da gamba, Jarmila Boonstra dance)

Folias by Camarata Delft

Duration: 4'39" direct link to YouTube

© 2022 by Camerata Delft- Title: La Folia

- Published at YouTube 2 Decemer 2022

- Duration: 4'39"

- Recorded live in Restaurant/ & Eetcafé De Waag, Markt 87, Delft, The Netherlands, 28 September 2022

'Chaconne' as part of 'Dancing' (édition Henry Lemoine), a suite in four parts (1 Rag-tango, 2 Chaconne, 3 Fly Dance in the night, 4 Chicken rock)

The chaconne follows rather accurately the Folia chord progression throughout the piece. The repetitive character reminds me of the Folia by Ian Krouse. A piece that instantly pops up in my mind listening to Chaconne is "Continuum" by Gyorgy Ligeti a classical in the contemporary repertoire for harpsichord, another instrument with plucked strings. Although plucked strings cannot create a continuous motion of legato, the very fast repetition of tones, resulting in three wavelike movements, suggests that such an impression can be created in Chaconne.

- Trio Polycordes: Isabelle Daups (harp), Jean-Marc Zvellenreuther (guitar),

Florentino Calvo (mandolin) 'Volume 2'

Trio Polycordes wrote for the slipcase (in a translation by E. Doucet):

Duration: 3'13", 2938 kB. (128kB/s, 22050 Hz)

Chaconne, the entire piece as part of 'Dancing'

© 2002 Régis Campo/La Follia Madrigal, used with permission

Carrying out an adventure, sowing long-lasting seeds is what the Trio Polycordes intends to do with this second record, focusing on the creative processes at a given time in a sort of inventory of today's musical praxis. The first recording recounted the genesis of an ensemble and a repertoire. Now time has come to develop both a story and an identity, to lay solid foundations. This second record aims at clearing a musical "terra incognita", giving each instrument the opportunity to reveal itself, making sure this shared land will be flourishing. Régis Campo's filiation can be traced back to the Baroque age . He pays a tribute to this musical tradition and at the same time perpetuates and renews it. Dancing is closely related to the "Suites de danse" made famous by composers such as Couperin or Rameau but Campo adds his own touch of night club atmosphere. The work is built round a glorious and luxuriant Chaconne. The theme of La Follia, clearly brought out at the outset, is gradually blurred by rich arabesques but can still be heard distant and faint as in a dream. Main panel of a contemporary altar-piece, this brilliant part is enhanced by the extremely minimalist movements that surround it. The first of them - Rag-Tango - is a double humorous reference. Regis Campo follows both Rag Time's spasmodic rhythm and the glissandos of the double-bass typical of a tango band. This unlikely mixing results in a strange ballet of sounds, a poetical evocation in which the dancers' steps on the stage may be heard through muffled notes. The last two movements belong to the tradition of animal paintings or that of the bestiary. Fly Dance in the Dark pursues the trill of the Chaconne and turns it into a key element in that behavioural study of flies' life. The buzzing insects induce a progressive fall into drowsiness in the listener. It's a lazy summer day's rest. But hey! What sheer pandemonium at the beginning of the fourth movement! Clucking, squawking, cackling, flapping of wings wake us up in an infuriated henhouse. Chicken Rock is a true, boisterous, gallinaceous Woodstock.

- Title: Dancing, (éditiopn Henry Lemoine)parts: 1 Rag-tango 2 Chaconne, 3 Fly Dance in the night, 4 Chicken rock. Chaconne is derived from the later Folia theme

- Released 2002 by La Follia Madrigal compact disc LFM11101, barcode 3 760023 510081 French distributor : EPI

- Duration: 3'13"

- Recording date: November 2001 at La Cave Dîmière, Argenteuil, France

- Revel, Jean-Christophe 'La Musique aujourd'hui: Régis Campo'

Régis Campo wrote in March 1999 for the slipcase:

Duration: 2'50", 2604 kB. (128kB/s, 44100 Hz)

Sonate la Follia, the entire piece

© 1999 Régis Campo/Jean-Christophe Revel, used with permissionThe Livre de Sonatas ('Book of Sonatas') for organ groups several commissions from the Spanish Ensems 97 festival, the city of Auch and Radio France. Composcd between 1997 and 1999, this is the fruit of a wonderful. lasting oollaboration with the young Frcnch organist Jean-Christophe Reve1. Each sonata is conceived in a single movement developing a single idea, in the manner of Domenico Scarlatti's sonatas or, better yet, Rameau's harpsichord pieces. L'extravagant is a sort of mechanical fantasy mingled with obsession ansd false naïvete. Le Don and La Nuit are the two most nocturnal sonatas of the cycle, the second, of course, being dedicated to the great master Vivaldi, whereas La Follia makes use of the famous 15th century dance. [...]

.- Title: Sonate la Follia (1998) from Livre de Sonates for organ

- Released October 1999 by Mandala compact disc MAN 4948 (distribution Harmonia Mundi)

- Duration: 2'50"

- Recording date: January 1999 in church of Saint Ferdinand des Ternes, Paris, France

- Publisher : editions Henry Lemoine, Paris, France

- Rouet, Pascale 'Autour de l'Espagne'

Régis Campo wrote for the slipcase:

Régis Campo wrote for the slipcase:

The sonata 'La Follia' is taken from my 'Livre de Sonates' composed betwen 1997 and 1999 for the benefit of the young organist Jean-Christophe Revel. This 'Livre' gathers together several orders from Radio France, the Spanish festival Ensems at Valencia, and the Association of the Friends of the Organs at the cathedral of Auch.

Each Sonata, built in a single movement and developed around one theme only, is a reminder of Scarlatti's Sonatas or Rameau's Pieces for the harpsichord. Sonata no. 4 'La Follia' brings back the famous 15th century dance in a somewhat ironical and outmoded way. Pascal Rouet gives us a dynamic and personal version, highly consistent with the forceful spirit of my music.- Title: Sonate no. 4 'La Follia' (Edition Lemoine) for organ

- Released 2003 by Pavane Records compact disc ADW 7468

- Duration: 2'29"

- Recording date: July 2-4, 2001 in l'Abbatiale B-D de Mouzon, France

- Borbye, Anders 'Refolia, contemporary works for guitar'

Régis Campo wrote for the slipcase:

Régis Campo wrote for the slipcase:

This version for guitar was written with the help of the French guitarist Jean-Marc Zwellenreuter. I was looking for a very playful sound, Baroque in character and with humour and wit. This version is very different from the original version for organ with respect to texture and dynamics. I like the idea of the bottleneck in this piece; it is a good example of my ludic musical style.

- Title: Sonate la Follia (1998)

- Released October 2008 by Gateway compact disc AB001

- Duration: 3'28"

- Recording date: August-September 2008 in the Frederikskirken, Aarhus

- See the page Recommended Folia recordings

- More about Anders Borbye at http://www.andersborbye.dk

- Zvellenreuther, Jean-Marc 'Folias'

Jean-Marc Zvellenreither (translation into english by Atez Eloiv) wrote

for the slipcase:

Jean-Marc Zvellenreither (translation into english by Atez Eloiv) wrote

for the slipcase:

Régis Campo made a new Folia-version, in the spirit of composers of the 17th century, who didn't hesitate to transcribe their works for different instrumental formations. After the presentation of the theme in a rather baroque style, the composer uses different modes in the aim of disarticulating the phrase and introducing different kinds of interferences. The long development in harmonics was suggested by Régis Campo by a cadence in a concerto for guitar by Villa-Lobos.

- Released 1999 by La Follia Madrigal compact disc LFM099900

- Duration: 2'56"

- Recording date: September 1999 at La Cave Dîmière, Argenteuil France

Little is known about this group who performs popular songs in Italy near the border of Austria. I tried to contact them in English but I guess their English is even worse than my Italian. The Folia-performance consists of 3 times the Folia theme (16 bars) and ending with another 8 bars of the ending of the Folia with some modulation. The instrumentation and way of humming the notes is in a very folky way (a setting of a party with a campfire would be an excellent ambiance I suppose). Although the vocal parts are dominant no words are articulated, pure mouth music accompanied by mandoline, accordeon, some winds and drums in the background.

- Canzoniere del Progno 'Tornarà el tramvai'

- Released 2005 by unknown company with unknown order number.

- Duration: 1'14"

- Recording date: unknown place and date of recording

- More about this ensemble in the Italian language at http://www.canzonieredelprogno.it/

|

Folías Españas (Follies of Spain) for piano |

- Carbajo, Víctor

- Released 2017 by Carbajo, Victor for ILSMP

- 17 Variations, 16 pages of A4 format

- Duration: 6'30"

- Publishd at YouTube by Victor Carbajo 19 January 2018 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hUaRXklCUQ0

- The sheet music can be found in the ILSMP Library https://imslp.org/wiki/File:PMLP736921-carbajo-follies_of_spain-2016-pf.pdf

- Website of the composer: http://www.carbajo.net/obra/obra-2016-i.html

Work commissioned by Solisti Aquilani

Mauro Cardi wrote about his composition in the Italian language at his website:

La Follia è uno di quei temi la cui origine si perde nella notte dei tempi, spingendoci a ritroso, in Portogallo, almeno fino al XV secolo, per arrivare fino ai nostri giorni, dopo aver attraversato tutta la storia della musica, con centinaia di versioni e variazioni sul tema. Nel mio lavoro il riferimento è soprattutto alle versioni della Follia date da Marin Marais nelle Variazioni “Les Folies d’Espagne” e da Georg Friedrich Händel nella Sarabanda dalla Suite in Re minore. Sul tema della Follia si reggono alcune campate che sostengono il pezzo, strutture di otto misure, o multipli, in cui spesso il frammento diviene un materiale che si dispone anche verticalmente, arrestando il flusso melodico-armonico, raggelandolo in cluster, diatonici, o creando scie sonore che prolungano la memoria tematica e che conducono lentamente l’ascolto altrove, pur evocando un’illusoria caleidoscopica staticità.

Dalla Follia diventa poco alla volta impossibile liberarsi, questa è l’esperienza che ne ho fatto. C’è infatti una forma ossessiva nel tema che attraversa tutto il pezzo, una follia lucida, straniante, ipnotica nel suo ruotare sempre intorno a se stessa. Nomen omen.

La viola d’amore è accordata in maniera tradizionale (La Re La Re Fa La Re), mentre le sette corde di simpatia contengono anche due note eccentriche, Mib e Sib.

- Solisti Aquilani (with Luca Sanzò viola and viola d'amore)

- Première 15th February 2017, Auditorium del Parco, L'Aquila, Italy

- Repeat: 16th February 2017, Accademia Filarmonica Romana, Teatro Argentina, Roma, Italy

- Duration: ca. 15'30"

Patrick Cardy wrote about this composition:

La Folia is a set of variations for chamber orchestra, commissioned by l'Ensemble du Jeu Présent, with the assistance of the Canada Council. La Folia was one of the most popular bass progressions used for sets of variations, songs and dances in the late Renaissance and Baroque eras. Its origins are obscure, although it probably originated in Spain or Portugal some time in the early 16th century, from whence it spread to Italy, France and England. It goes under many names in many countries - la folia , la follia , les folies d'Espagne and Farinel's Ground , among others. And it is often, though not always (and not in this piece), associated with a standard discant melody. Some of the more famous treatments of la folia include a set of keyboard diferencias by Antonio de Cabezön (1510-66), a set of variations for violin by Michel Farinel (1685), the masterly set of 24 variations in d, Op. 5, No. 12, for violin and continuo, by Archangelo Corelli (1700), and the Sonata in d, Op. 1, No. 12, for two violins and continuo, by Antonio Vivaldi (1705). In La Folia a variant of the original bass progression is woven, usually very audibly and clearly, but in many different voices and textures, into the fabric of each variation.

The oeuvre of Patrick Cardy can be found at http://www.carleton.ca/~pcardy/- Cardy, Patrick

- Score of La Folia for string orchestra (for sale or on free library loan) and parts (rental only) are available from: The Canadian Music Centre, 20 St. Joseph Street, Toronto, Ontario, M4Y 1J9, tel.: 416-961-6601, fax: 416-961-7198, e-mail info@musiccentre.ca, webside: www.musiccentre.ca or www.centremusique.ca

- The score is 101 pages (plus title page and instrumentation/performance note page); full size, it is 11"x17", but the Canadian Music Centre can also reproduce it in smaller sizes.

- 14 parts (flute/piccolo,oboe, clarinet in Bb, bassoon, horn in F, trumpet in Bb, trombone, percussion (one player: triangle, high sizzle cymbal, medium cymbal, low cymbal, crotales, glockenspiel, vibraphone, tam-tam, bass drum), piano/celesta, violin I, violin II, viola, violoncello, contrabass), reproduced in booklets on standard 9-1/2"x12" sheets.

- l'Ensemble du Jeu Présent/Bellomia, Paolo conductor

- Premiere November 2, 1997 (place unknown), recorded for broadcast on Musique Actuelle (TBA) May 15, 1998

- Duration: 16'00"

- Recording date: May 15, 1998 in the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

- Grupo Koan, conducted by José Ramón Encinar, violin solo

Luis Navidad

- Released by unknown

- Duration: 9'10"

- Recording date: March 4, 1980 in the Casa de la Radio de Radio Nacional de España, Prado del Rey

- Orchestra da Camera del Cantiere, conducted by José Ramón

Encinar

- World premiere

- Recording date: August 9, 1978 in Montepulciano, Italy

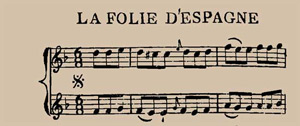

Originally published in IIIeme Recueil de menuets, allemandes, et contredances, avec vingt et une variations des Folies d'Espagne, touttes en pincés différents, et d'un genre nouveau, entremêlés d'ariettes avec leurs accompagnements pour le cythre, ou guitthare allemande, qui peuvent néantmoins s'exécuter sur la Mandore et sur la guitthare espagnole..., edition Paris, 1771

|

Duration: 3'54", 11 kB. |

- François Castet 'Collection Renaissance , Musique Française pour guitare Vol VI'

- Published 1968 by Georges Delrieu & Cie., Nice

- Order number G.D. 1415

- 4 pages in modern sheet music, created after the original tablature

- Collection Dr. D.F. Scheurleer (inv. 7388 Royal Library, Den Hague, Netherlands)

- Title: IIIeme recueil, de menuets, allemandes et contredances : avec vingt et une variations, des folies d'Espagne, touttes en pincés differents, et d'un genre nouveau, entremelés d'ariettes, avec leurs accompagnements : pour le cythre, ou guitthare allemande, qui peuvent neantmoins s'executer sur la mandore et sur la guitthare espagnole / par Mr Carpentier Chan. de St. L. du Louvre amateur

- Published by Le Marchand, Paris, France

- Size 26 pages, 33 cm

- Le Concert Impromptu (oboe, clarinet, bugle, bassoon and flute) 'Nouvelles

folies d'Espagne'

- Released February 2002 by Aime La Belle Records compact disc without order number

- Duration: c. 20'

- Recording date: February 2002 in Temple St Marcel, Paris, France

Michael L. Carroll wrote about his Variations on Folias for String Quartet:

I just composed a new variant of the Folias. These are "loose" variations in that I allowed myself to modulate to other keys and to insert a parallel major version of the Folias chord progression. The piece starts in D minor and is written in 17th century style counterpoint and gradually evolves into a more modern treatment with modulations to a variety of keys and ending in D major. Although my variations are based on the Folias chord progression, nowhere in the piece do I actually quote the Folias melody The playing time at 100 bpm should be about 6 minutes. I was inspired to write this after seeing the Folias-website. The PDF score and an mp3 file are attached.

- Carroll, Michael L.

All Variations on Folias created with Finale (GPO) by Michael L. Carroll

Duration: 5'58", 2451 kB. (56kB/s, 22050 Hz)

© 2009 Michael L. Carroll, used with permission

Variations on Folias in pdf-format, size 60 Kb

The complete sheet music

© Michael L. Carroll 2009, used with permission.- Published 2009 by Michael L. Carroll

- Soundfile generated from within Finale using the Garritan Personal Orchestra (GPO). Although the samples sounds of the GPO are vastly superior to the ordinary, monotonous synthesized MIDI sounds, there is nonetheless a computer-generated feel to these. They sound much, much better, of course, with real human performers. This file is only intended to give you an idea.

- Duration 5'58"

- Score 12 pages for 4 instruments (violin 1, violin 2, viola and cello)

- More about the oeuvre of Michael L. Carroll you can fin at http://www.musicarroll.com/

Michael Carroll wrote about his Theme and Canonic Variations on Folias of Spain in an e-mail the 13th of March 2015:

I've completed another folias composition, this time a duet for two guitars. It starts off with the traditional folias with variations in d minor and then modulates to a minor where it presents variations on a different chord progress but similar in some ways to the folias; then it modulates back to d minor and the folias chord progression for a short reprise.

You have my permission to post on the Fol website.

- Carroll, Michael L.

Theme and Canonic Variations on Folias of Spain in pdf-format, size 70 Kb

The complete sheet music for two guitars

© Michael L. Carroll 2015, used with permission.

Theme and Canonic Variations on Folias of Spain in pdf-format, size 60 Kb

The complete sheet music for guitar I

© Michael L. Carroll 2015, used with permission.

Theme and Canonic Variations on Folias of Spain in pdf-format, size 60 Kb

The complete sheet music for guitar II

© Michael L. Carroll 2015, used with permission.- Published 2015 by Michael L. Carroll

- Soundfile generated from within Finale using the Garritan Personal Orchestra (GPO). Although the samples sounds of the GPO are vastly superior to the ordinary, monotonous synthesized MIDI sounds, there is nonetheless a computer-generated feel to these. They sound much, much better, of course, with real human performers. This file is only intended to give you an idea.

- Duration 7'03"

- Score 9 pages for 2 guitars and two parts (4 and 5 pages)

- More about the oeuvre of Michael L. Carroll you can fin at http://www.musicarroll.com/

- original manuscript in Biblioteca Musicale Greggiati Ostiglia

- Sebastiani, Adriano 'The Complete Edited Songs for Voice and Guitar'

- Title: Les Folies d'Espagne variées Op. 75 in D minor (for solo guitar)

- Released January 1, 1996 by Dynamic compact disc 124

- Duration: 7'31"

- Recording date: 12-12 September 1994, Florence

- Soloist: Adriano Sebastiani

Salvador Castro de Gistau, originally from Madrid became editor of the "foreign music" magazine 'Journal de Musique Etrangére pour la Guitare ou Lyre' in this Paris

- Castro de Gistau, Salvator

Theme and 9 var. in pdf-format, size 2.44 Mb

The facsimile sheet music for guitar

© The Royal Irish Academy of MusicOpening of Variations de Las Folias d'Espagne from the original publication

- Title: Première partie: theme and 9 variations

- Published in: Journal de Piéces de Musique pour la Guitarre Tirées de divers Auteurs Espagnols & autres; Publié par S. Castro (de Gistau) No 16

- Published unknown year by Salvador Castrode Gistau (l'Éditeur et l'Auteur) in Paris, France

- 4 pages

- Original source available at the internet by The Royal Irish Academy of Music Call no:H.XXXVIII.10.(37) (Hudleston Digital Library)

- Grohen, Markus (re-published the score)

Duration: 0'39", 02 kB.

The opening as indicated in the sheet music belowOpening of Variations de Las Folias d'Espagne Published in 'Guitarre & Laute', 1995

- Published by the German Magazine 'Guitarre & Laute', Jahrgang XVII, heft 6, 1995

- Score 14 p., 29 cm

- Vandecauter, Herman (guitar)

As far as I know this is a worldpremiere recording of an old manuscript in a high quality performance.

As far as I know this is a worldpremiere recording of an old manuscript in a high quality performance.

La Follia by Herman Vandecauter

Duration: 6'41" direct link to YouTube

© 2015 by Herman Vandecauter- Title: La Follia (première partie: theme and 9 variations)

- Published at YouTube May 2015 by Herman Vandecauter

- Duration: 6'41"

- Recorded May 2015 in Belgium

- For the website of Herman Vandecauter see: http://www.earlyguitar.be/

- La Cetra d'Orfeo: Didier Laloy (diatonic accordion), Michel Keustermans (recorder and director), Hervé Douchy (violoncelle), Jacques Willemijns (harpsichord), Jurgen De Bruyn (theorbo and baroque guitar),

Stephan Pougin (percussion), Laura Pok (recorder), Ingrid Bourgeois (violon).

Duration: 1'27", 1.4 Mb. (128kB/s, 44100 Hz)

Fragment of Poule Noir

© 2007 La Cetra d'Orfeo, used with permission

Michel Keustermans wrote for the slipcase (translation by Rachel Stacchini-Betton-Foster):

Michel Keustermans wrote for the slipcase (translation by Rachel Stacchini-Betton-Foster):

Finally, it was difficult to resist this last temptation: our Walloon Folklore has an abundance of tunes going back to the beginning of time, and 'Poule Noire' (Black Hen) is nothing if not an authentic Folia which has come down the ages through popular dancing.

- Title: Poule Noire (black hen), unfortunately no sources mentioned for this tune

- Released 2007 by EOLE compact disc EAD002

- Duration: 3'25"

- Recording date: May 2006 at Chapelle du Bois

- See also the page Recommended Folia-recordings

- Chatham Baroque (Julie Andrijeski baroque violin, Patricia Halverson viola da gamba, Scott Pauley theorbo and baroque guitar)

with guest artists Daniel Mallon percussion and Becky Baxter harp

Folias by Chatham Baroque with guests live

Duration: 10'34" direct link to YouTube

© 2011 by Chatham Baroque- Title: Folias

- Broadcasted by unknown radiostation

- Duration: 10'34"

- Recorded live March 11, 2005 in St. Paul's United Methodist Church, Houston, United States as part of the Houston Early Music Series

- See for the program: http://www.houstonearlymusic.org/hemarchive/archive/2004/chatham.htm

Set of twelve variations on the Folia theme for brass quintet (Trumpet in C1, Trumpet in C2, Horn in F, Trombone, Tuba)

A very nice and transparent composition for brass quintet. Somewhat in the idiom of the Folia variations by Jan Bach, which I consider as one of most interesting and enjoyable efforts to translate the Folia theme to modern times. The nice thing of a brass quintet is that the voices are so clear that the listener can distinguish the action and interaction bewteen the voices. Further on the Folia theme has a somewhat fragile setting with that modest melody line but the brass instruments transform the music into a very powerful statement especially with those firm trumpets. Those intriguing features strike me again when listening to the music of Jean Chatillon with his Fantaisie sur La Folia

Jean Chatillon wrote about his Fantaisie sur La Folia:It was after listening to the fine compositions of my two friends of the Delian Society (editor: Thomas Matyas and David W. Solomons) that I became intoxicated by this tema.

- Chatillon, Jean written in Finale2005

Duration: 7'58", 7.56Mb. (128kB/s, 44100 Hz)

The complete set of variations

© 2009 Jean Chatillon, used with permission

Fantaisie sur La Folia, 22 pages in pdf-format, size 255 Kb

The complete sheet music

© Jean Chatillon 2009, used with permission.- Title: Fantaisie sur La Folia

- Duration: 7'58"

- Published by Editions de l'Ecureuil Noir, Becancour, Canada

- 22 pages, size 21 x 29 cm (and 5 parts)

- More about the composer and his compositions at: http://www.jeanchatillon.com/

- Musicians from Budapest (Hungary)

Musicians from Budapest

Duration: 8'20" direct link to YouTube

© 2009 and 2018 by Jean Chatillon- Title: Variations sur La Folia pour quintette de cuivres

- Duration: 8'14"

- Published by Jean Chatillon, 13 October 2018 at YouTube

- Recorded August 2018

- Link to the YouTube performance https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jJOO8h0RrxM

- Ensemble Oni Wytars 'La Follia, the triumph of Folly'

Great performance with the unusual nickelharpa to give the tune a Scandinavian setting.

Great performance with the unusual nickelharpa to give the tune a Scandinavian setting.

- Title: Les Folies d'Espagne

- Released 2013 by Deutsche Harmonia Mundi compact disc 88765449782

- Duration: 2'44"

- Recording date: October 1-3, 2011 in Kurtheater, Bad Kissingen, Germany

- See also recommended recordings

- Van Kerckhoven, Pieterjan & Van Troyen, Bart (bagpipes)

Ever heard two bagpipes play the Folia in full harmony?

Pieterjan Van Kerckhoven and Bart Van Troyen

Duration: 7'50" direct link to YouTube

© 2013 by Pieterjan Van Kerckhoven and Bart Van Troyen- Title: Les Variations Amusantes Les Folies d'Espagne

- Released 2013 at YouTube by Bart Van Troyen

- Duration: 7'50"

- Recording date: 2013

- Bagpipes (musette) built by Remy Dubois

In the opening of the ouverture the folia-theme is several times ingeniously quoted, even in a somewhat fugative style.

- Academy of St. Martin in the Field/Mariner, Sir Neville 'Cherubini:

Ouvertures'

Basil Deane wrote in 1992 for the slipcase:Sometimes there is a historical reference - the use of the traditional theme 'La folia'in L'Hotellerie portugaise

.- Released 1992 by EMI CLASSICS compact disc CDC 7544382

- Duration: 9'43"

- Recorded 1991 in Studio Abey Road London, England

- City of Birmingham Orchestra/Foster, Lawrence 'Luigi Cherubini Ouvertures'

From the slipcase:

From the slipcase:

L'Hôtellerie portugaise, one of three one-act opéras comiques written in 1798 and 1799, is based on the familiar plot of the lovers who have to outwit the old guardian bent on marrying his pretty young ward himself. Set in an inn on the border between Spain and Portugal, the story this time moved Cherubini to make a discreet application of local colour, in the form of allusions to the popular Portuguese tune La Folia, in the slow introduction to the ouverture. The main Allegro section is a skilfully achieved accumulation of eager expectation which reaches its climax just before the end.

- Released 1996 by Claves Records, Switzerland compact disc CD 50-9513

- Duration: 11'58"

- Recording date: 5-6 February and 20 June 1995 in Birmingham, Town Hall

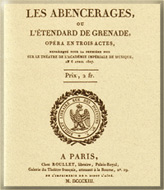

Nowadays this opera has sunk into almost complete oblivion and this may be the main reason that the quite substantial Folia in the Ballet in act 1

is never mentioned in the Folia literature, although the opera itself was the subject of a recent

dissertation. Fortunately a live recording of this opera from 1956 exists, although of an absolute poor quality.

In fact the Folia-theme in Les Abencérages is more prominently stated and worked out in variations throughout the above mentioned

Ballet than in the Ouverture from L'Hôtellerie portugaise. But fate decreed that it was the Ouverture that established Cherubini's fame

in the Folia literature; for instance in the New Grove Dictionary of music and musicians.

Nowadays this opera has sunk into almost complete oblivion and this may be the main reason that the quite substantial Folia in the Ballet in act 1

is never mentioned in the Folia literature, although the opera itself was the subject of a recent

dissertation. Fortunately a live recording of this opera from 1956 exists, although of an absolute poor quality.

In fact the Folia-theme in Les Abencérages is more prominently stated and worked out in variations throughout the above mentioned

Ballet than in the Ouverture from L'Hôtellerie portugaise. But fate decreed that it was the Ouverture that established Cherubini's fame

in the Folia literature; for instance in the New Grove Dictionary of music and musicians.Paul Korenhof wrote for the slipcase

The premiere of Les Abencérages took place at the Paris Opéra on 6 April 1813 in the presence of Napoleon and his wife and it proved one of the greatest successes of Cherubini's career.

- Orchestra di Theatro Comunale di Firenze conducted by Carlo Maria Giulini 'Gli Abencerragi'

- Released 2002 by Gala compact disc GL 100577 2cd-set

- Duration: 8'50"

- Recorded May 9, 1956 in Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, Florence, Italy

- Orchestra sinfonica di Milano conducted by Peter Maag 'Les Abencérages'

Gian Andrea Lodovici wrote for the slipcase:

The fact that this was one of Cherubini's most successful operas is confirmed not only by the enthusiastic comments of the many personalities present at the first performance, including Napoleon and Marie. Louise, but paradoxically also by the request made by the composer himself after about twenty performances that the dramaturgical part of the opera be cut and reduced into two acts in order to create more space for ballets. A practice reserved in France only for those operas that sought to becomepart of the "repertoire" [...]

To hear again the French version of 'Les Abencerages, however, we had to wait for the radio production of 15th January 1975 which Peter Maag and Radio Italiana chose to perform. This is a production that returned to the original three-act version of the opera, with limited use of ballets, and is proposed without significant cuts compared to the radio performance tradition of the time.- Title: Danses (cd 1: track 13)

- Released 1975 by MRF Records MRF/C-07 (C-071 - C-072) 2 lp-set and remastered 24bit/96kH by Archives January 2006 for a 2-set compact disc 43066-2

- Duration: 3'06"

- Recording date: January 15, 1975 in Milan, Italy

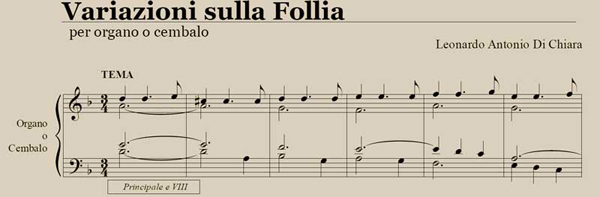

Antonio wrote in the preface of his composition (here indicated in an English translation):

The idea of ??composing variations on the famous theme of Folía (madness) was born from the proposal made to me by the dedicatee of this composition il Maestro Sergio De Blasi. I took the proposal with great pleasure as the theme Follía is a theme that has always fascinated me. The structure of the entire composition is spread over 15 variations of which the last is a 3-part escape and can be performed both on the harpsichord and on the organ. As for the organ it can be safely performed even on an ancient organ, leaving the performer free to eventually fill some parts with the pedals. The indication of the registers indicated in the score is not intended to be binding, but only a small idea of ??how I thought the song phonically, therefore the performer is left full freedom and imagination. The harmonic system of the piece develops on harmonies deriving from the superimposition of fourths and fifths for most of the song. While in the latest variations I preferred to use gradually a return to harmony classical-tonal and it seemed interesting to me, at the end of the song, to make the theme of Follía with the usual classical harmonic relationships, so that the listener can also elaborate a "pleasant musical journey" that with a modern style start leads to a more classic style. In conclusion I tried to be adherent to my style, but at the same time to turn my gaze towards the past, with the hope that these pages will enter the repertoire of organists or harpsichordists.

- Leonardo Antonio Di Chiara (organ or harpsichord)

- Title: Variazioni su tema della Follía per organo o cembalo

- Published June 2020

- 14 Pages, A4-Format, 368 bars.

- More about the composer at his homepage https://www.leonardoantoniodichiara.com/

- You can find the YouTube page of Leonardo Antonio Di Chiara at https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCQXg8Dxd4Nb1Ko8fjYfvFWg

Bernard de Chiacourt seems to be living in the sourtern part of the Dutch Republic.

- Inventory NMI92.0 Royal Library, Den Hague, The Netherlands

- Title: Folies d'Espagne, variés pour la flûte avec accompagnement de violon et basse

- Published 1816 by Plattner (based upon the names Eitner and Mazure), Rotterdam, The Netherlands

- 2 parts, 33 cm

Classical crossover group CJA (pronounced see-jay) consists of Joanne Jolee (vocals and keyboard and her three daughters, Christine (violin), Leiticia (vocals and violin) and Krystle (vocals and cello). CJA's musical style is an alchemic blend of European pop, fused with the likes of J.S. Bach and Scarlatti, Celtic folk songs, traditional Irish fiddling and spiritual and poetic influences, as well as disco, opera and techno-industrial elements.

- CJA (drums: Bill Jaffa, piano and vocals: Joanne Jolee, violin: Christine Adkins, violin and vocals: Leiticia Pestova, cello and vocals: Krystle Delgado) 'Things Have Changed'

- Title: Kissings: lyric - 'Love's Philosophy' by Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822), music - La Folia, 16th Century

- Released 2006 by Pinnacle American Records compact disc LCC 837101274555

- Duration: 4'52"

- Recording date: unknown

- More information about Joanne Jolee and about this recording you can find at http://www.joannejolee.com/joannejolee-Kissings.htm

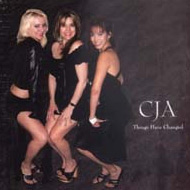

Collector of music. Was an excellent dancer and violinist so most probably the La Folie d'Espagne was intended for two violins.

|

La Folie d'Espagne in 26th Recueil de Contre-danses et Waltzes. page 20 and 21 |

| Opening of La Folie d'Espagne | Published ca. 1810 |

|---|---|

|

|

- Clarchies, :Louis-Julien

- Title: La Folie d'Espagne

- Published in 25th Recueil de Contre-danses et Waltzes, page 20 and 21

- Published by Fr`re, Paris, n.d. [ca.1805-1815]

- Published in ILSMP 2013 by Pierre Chepelov

|

Somalia in pdf-format, size 37 Kb |

Somalia by Gintonic |

This is a composition I've made for my jazz-rock band Gintonic. It's based on the Follia (the Intro is the Pasamezzo Antiquo). It's very recent so I don't hace still the audio. I hope i will send you in a couple of months. I play flute and EWI in the jazz-rock band Gintonic.

Although I play mainly jazz - rock by now, my beginnings in music were in the field of early music. I have play many sets of variations upon the Folia (Vivaldi, Marin Marais...) with the recorder. I think the Folia and the Blues (as schema, the 12 measures) are the major cathedrals in music. I've write this music as a reaction to the human disaster in Somalia (the last 3 letters are the same -lia)

Of course, It's possible to publish the sheet music in your website.

Somalia is based on this schema:

Intro: 8 bars (Pasamezzo antiquo)

Theme: Folia (Am7 - E7#9 - Am7 - G9 --- CMaj7 - G9 - Am7 - E7#9 --- Am7 - E7#9 - Am7 - G9 --- CMaj7 - G9 - Am7-E7#9 - Am7) 2 times

Guitar open solo (E7#9)

Intro: 8 bars (P.A.)

Theme: Folia 2 times

Flute solo: second half of Folia many times

All the chords are "jazzified" i.e. (instead of Am-E-Am-G, I've write Am7-E7#9-Am7-G9) but the chord progression of the main theme is the Folia in A minor.

In the future I will send you the link of YouTube with this music.

- Clavell Larrinaga, Mario

- Title: Somalia

- Published 2012 by Mario Clavell Larrinaga for Gintonic (Mario Clavell Larrinaga - flute, Ramón Escobar - guitar, Dabid Martín - fretless bass, Gorka Díez - drums)

- Duration: 3'55"

- Sheet music 1 page (just the framework of the tune for improvisation)

- More about Mario Clavell and Gintonic at http://www.myspace.com/gGintonic4t

- Cardoso, Jorge (guitar) 'Tanidos, Musica Barroca Española'

The complete theme and variations as played by the maestro Jorge Cardoso

Duration: 13'23", 15.6 MB. (160kbs, 44100Hz)

© Jorge Cardoso 1988, used with permission- Title: Folies d'Espagne

- Released 1988 by TecnoSaga vinyl MSD 4004 and re-released 1992 by Several records 2-cdset

- Duration: 13'23"

- Recording date: 1988 at Several records, Madrid, Spain

- Prix du Ministère de la culture Spain in 1991

- More about this piece in the French language at http://www.vlamarlere.com/article-20067786.html

- More about this maestro on the guitar at http://guitarreando.iespana.es/cardoso.htm

- Cicero, Rosario (baroque guitar) 'Danzas de Rasgueado y Punteado'

Rosario Cicero (translated by Andrea Manchée) wrote for the slipcase:

Rosario Cicero (translated by Andrea Manchée) wrote for the slipcase:

It's in the Folies d'Espagne by Le Cocq that we find a compendium of the language of the baroque guitar, in an aesthetic and idiomatic synthesis of the subdued and rarefied folk influences, the peculiarities of a more elaborate performing technique and the profound expressive idiom of musical culture in the baroque era.

- Released 1999 by Nìccolò Guitart collection, Italy compact disc NIC 1009

- Duration: 8'26"

- Recording date: February 1999 at Jambling Studios - Nola (Na), Italy

- Cicero, Rosario (baroque guitar) 'Danzas de Rasgueado y Punteado'

- Released 2002 by GuitArt (magazine), Italy compact disc GUIT 2028

- Duration: 8'26"

- Recording date: February 1999 at Jambling Studios - Nola (Na), Italy

- Mirarchi, Francesco (baroque guitar)

Live performance by Francesco Mirarchi

Duration: 3'44" direct link to YouTube

© 2013 by Francesco Mirarchi- Released May 2013 by liberiamolabellezza for YouTube

- Duration: 3'44" (abbreviation)

- Recording date: 2013

- Recueil des pieces de guitarre, p. 74-81 (facsimile publication)

- Published by: Thesaurus musicus. Brussells: Edition Culture et Civilisation

- Year: 1979

- Storms, Yves (guitar) 'Variations Folia de España'

Peter Pieters wrote as introduction to Folies d'Espagne on the inside

of the cover:

Peter Pieters wrote as introduction to Folies d'Espagne on the inside

of the cover:

In Baroque times, no melody or chord schema was more often used in variations than the Folly from Spain. Incontestably, Corelli's «La Folia» is the most famous, but even ].S. Bach used the theme' in his «Peasant Cantata».

Originally, the Folly was a wild dance, in which men in carnival costume often ~eached a state of hysterical trance. The Church did not approve and as a result the Folly was gradually transformed into the slow, solemn melody we know today

The Folly was extremely popular among baroque guitar players, to the point that Robert de Visee - almost alone in not publishing one - felt it necessary to write in his introduction: «Neither will one find here the Spanish Folly. So many of these are now to be

heard, that I could only repeat the follie of others».

There is not the space here to list all the Follies written for the Baroque Guitar, but the three collected on this record are among the most beautiful: that of the Spaniard F. Gereau, the Brussels-born F. Le Cocq and the ltalian A.M.B. whose works have been neglect to this day.

In later times as well, guitar players have shown their partiality for the Spanish Folly and the two greatest guitar composers of the 19th Century, Fernando Sor and M. Giuliani, wrote variations on these themes. In our own times the Mexican Manuel Ponce, who wrote principally for the guitar, also composed some Follies; indeed, his most important work comprises no less than 20 variations followed by a majestic fugue.- Title: Les Folies d'Espagne

- Released 1983 by EMI Belgium 1A 065 1651791

- Duration: 7'30"

- Recording date not mentioned in the documentation

- See also the page Recommended Folia-recordings

- Takeuchi, Taro (5 course guitar) 'Folias!, virtuoso guitar music of

C17th on period instruments'

Monica Hall wrote for the slipcase:

Monica Hall wrote for the slipcase:

We are indebted to the Flemish clergyman and amateur guitarist, Jean-Baptiste de Castillion (1680-1753), whose activities as a music copyist have preserved the guitar music of François Le Cocq (fl.1685-1729), Nicolas Derosier (c.1645-1702) and many pieces by Corbetta not found in the surviving printed books. In the preface to the manuscript which he copied in 1730 (B:Bc.Ms.S.5615) Castillion says that in 1729 Le Cocq gave him copies of his music, which he re-copied for his own use, adding pieces by several other composers of the previous century. He says that Le Cocq taught the guitar to the wife of the Elector of Bavaria and refers to him playing to the sister of the Archduke Charles of Austria, later emperor Charles VI. This was probably Maria Antonia, a half-sister of Charles, who married the Elector Maximillian II Emanuel in 1685 and died in 1692. In 1729 Le Cocq is described as a retired musician of the Chapel Royal in Brussels. His variations on Folies d'Espagne is a technical tour de force featuring the 'harpegemens', elaborately arpeggiated chords, which were a jealously guarded secret of Le Cocq's. Castillion says that he rarely indicated them in his music so as to conceal how he played them and to preserve them to himself alone.

- Title: Folies d'Espagne

- Released 2002 by Deux-Elles Limited, Reading, UK compact disc DXL 1030

- 5 course guitar by Martyn Hodgson , Leeds 1982 after René Voboam, Paris, 1641. he original is in the Hill Collection, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

- Duration: 10'01"

- Recording date: April 16 and 17 at St Martin's Church, East Woodhay, England

This piece for one voice is listed as 'Follia' in the Tavola dell'arie at the end of the volume.

- Ensemble for the Seicento 'Forbidden dance, dance and diminutions of

the Italian Baroque'

- Title: Lauda Spirituale/Folias di Spagna (improvisations)

- Released 2001 by Musicians Showcase Recordings compact disc MS 1073

- Duration: 7'40"

- Recording date: January 2000 at St. Paul's Episcopal Church Brooklyn New York and January 1998 at Calvary Church, Parish of Calvary/St. George's, New York City

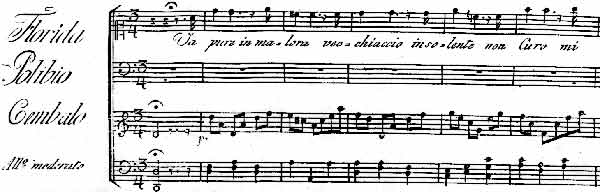

Oddly enough, the almost identical duet with a partly different text was used more than 70 years later as part of the opera 'La Pastorella Nobile', a production of Pietro Alessandro Guglielmi (1728-1804). The music of the duet was attributed on the title page of the Artaria print to 'Sig(nor). Conti' which might easily lead to Giacomo Conti, the violinist and composer who led the orchestra of the Burgtheater from 1793 but the music is almost identical to the earlier version of Francesco Conti. It is an indication how famous Francesco Conti was in the 18th century (there seems to be only one Sig. Conti, and the musical quality of the duet is indeed extremely high).

John A. Rice wrote in March 2006 about the differences between the duet in 'Don Chisciotte in Sierra Morena' and 'la Pastorella Nobile':

I've just looked at a manuscript full score of 'Don Chisciotte in Sierra Morena' in the Austrian National Library, Signatur Mus. Hs. 17207, published in facsimile by Garland, New York, 1982. The duet on La folia is at the end of act 2; it is entitled "Va pure in buon' ora". It is the same duet as the one inserted much later in Guglielmi's opera, with the following differences:

- In 'Va pure in malora' part of the text is different (but much of the text, including the long string of insults, is the same)

- The duet in 'Don Chisciotte' is in da capo form (A-B-A): the first part of the duet (up to the words 'mai non vi fu') is repeated after the second part (ending with the words 'per me sei tu'). So the duet ends in the same key (D minor) in which it began. In the later version the second A section is omitted, so the duet ends in a key (G minor) different from the key in which it began.

- 'Va pure in malora' ends with a short instrumental passage in G minor that is not in 'Va pure in buon' ora.'

- 'Va pure in buon' ora' begins with a short instrumental passage in D minor that is not in 'Va pure in malora.'

- I Piccoli Holandesi directed by Marc Pantus (with vocals by Anne Grimm, Renate Arends, Ricardo Prada, Marc Pantus)

with some new contemporary songs

- Performance: May 15, 2005 in Muziekgebouw aan 't IJ, The Netherlands

- Duration: 9'09"

- Recorded by De Concertzender, production www.harmonysound.nl

Duration: 0'59", 958 kB. (128kB/s, 22050 Hz)

Anne Grimm, Marc Pantus and the Utrechts Barok Consort conducted by Jos van Veldhoven

© 2005 Marc Pantus, used with permission- Premiere April 27, 2005 in Kampen, The Netherlands

- Duration: unknown

- Recorded by De Concertzender, broadcasted by Dutch Radio 4, Viertakt April 25, 2005

- Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin and Nederlandse Operastichting directed by René Jacobs 'Don Quichotte in Sierra Morena, tragicommedia in five acts, Vienna 1719'

.

.

- Casting duet: Judith van Wanroij (Maritorne) and Marcos Fink (Sancio Pansa).

- Duet at the end of the second act.

- Recording date: June 26, 2010 during the Holland Festival 2010 in the Stadsschouwburg, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

- Broadcasted by NPS radio 4 June 26, 2010 (live broadcasting of performance)

- Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin and Tiroler Landestheater directed by René Jacobs 'Don Quichotte in Sierra Morena, tragicommedia in five acts, Vienna 1719'

In the program was written:Live performance of Folia parts ending with the famou duet 13 Aug. 2005

Duration: 11'19" direct link to YouTube

© 2011 by Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin

Francesco Conti (1681-1732), now almost forgotten, was a very famous and highly respected composer in his time. The largest part of his life he worked at the imperial court in Vienna. In 1708 he was apointed first theorbo player, in 1713 he became also court composer. After these appointments he became one of the highest paid musicians in Vienna, who was able to perform his own works with the best singers, since he could pay them well. After falling ill in 1726 he returned to Italy, but in 1732 he returned to Vienna to introduce some new works. It is an indication of his reputation that his successor as court composer, Antonio Caldara, had to step aside to make place for Conti. Shortly thereafter Conti died.

The focus of the the 29th Innsbruck Festival of Early Music was the era of the Viennese Court Opera. Directed by René Jacobs, the opera "Don Chisciotte in Sierra Morena" was performed five times at the Tiroler Landestheater. National and international audiences and critics alike were enthusiastic about the young vocal ensemble which was accompanied by the Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin.

This work performed was composed for the Carnival season in 1719. It was extremely successful: it was even translated into German, and was performed 25 times outside Vienna, mainly in Hamburg. Don Chisciotte in Sierra Morena is a tragicommedia, which combines elements of the opera seria and the intermezzo (a form of comedy which was performed in between the acts of the opera seria as a form of compensation for the disappearance of all comic elements from the opera seria). It not only combines these elements, but also ridicules some elements of the opera seria. The way Conti portrays Don Quixote and Sancho Pansa in particular is brilliant. Don Quixote, a puffed so-called knight, who believes that he is a hero, and doesn't want to see the truth, even if it is right under his nose.

In Conti's time, Don Chisciotte lasted about 5 hours.

In Conti's time, Don Chisciotte lasted about 5 hours. Thusly, cuts were made in this performance which consumes just over 3 hours.- Casting duet: Fulvio Bettini (Sancio Pansa) and Gaêle Le Roi (Maritorne).

- Duration: Act 1: 8'40" instrumental and duets (55'53"), Act 2: 0'43" one instrumental variation (60'05") , Act 3: 1'52" three instrumental variations for concluding the act (42'20")

- Recording date: August 13, 2005 during the 29th Innsbruck Festival of Early Music 2005 Tiroler Landestheater, Innsbruck (the performance was also August 16, 22, 24, 26 at the festival)

- Broadcasted by unknown radio-station and posted in the newsgroup alt.binaries.sound.mp3.classical March 2006

- Elbipolis Barockorchester Hamburg 'Don Quichotte in Hamburg'

Jörg Jacobi wrote for the slipcase:

[...] Such conversations bore Don Quixote and especially Sancho Panza. They leaf through the music of Conti's opera, which he had brought with him. "Look, my dear Sancho, just look at this! Indeed, how marvelously our story is told," exclaims Don Quichote, " how wonderfully fresh the music - I like it! And it also has real Spanish character, even a follia!" Grumbling to himself he recalls the evening's opera performance of this miserable piece of work by Mattheson: "Granted, the music is nice, but the story is not at all the right thing for a Spaniard. here, on the other hand: A follia! A chaconne! A Ballo de Pagarellieri, a ballet of the squires, like Mr. Conti has composed it - this is something that is knightly and would certainly also please my Dulcinea!"

- Released 2005 by Raumklang compact disc RK 2502

- Duration: 2'20"

- Recording date: May 8-12, 2005 in 14943 Schönefeld/Marzahna

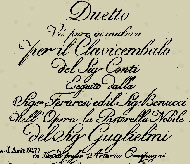

| Opening of Conti's Folia | Artaria publication for the opera La pastorella nobile |

|---|---|

|

|

John A. Rice wrote about this piece:

John A. Rice wrote about this piece:This is a printed keyboard vocal score of a duet composed by Conti used for the first Viennese production of Guglielmi's comic opera La pastorella nobile. The singers were Adriana Ferrarese (the first Fiordiligi in Mozart's "Cosi fan tutte") and Francesco Benucci (the first Figaro and Don Alfonso). The entire duet is based on La Folia; the text is probably by Lorenzo da Ponte. The first Viennese production of "La pastorella nobile" is discussed in my dissertation "Emperor and impresario: Leopold II and the transformation of Viennese musical theater, 1790-1792"

In the dissertation John A. Rice writes (p. 125):[...] Also added to the Viennese version in place of the recitative in the original was the duet for D. Florida and D. Polibio, "Va pur in malora," attributed in the Artaria print to one "Sig. Conti." (It is not clear that this duet was in fact sung as part of Guglielmi's opera. The text appears in the 1790 libretto, but a note at the end of the libretto informs us that the duet was omitted in performance; yet Artaria issued a keyboard reduction of the duet and described it as "eseguito dall Sigra. Feraresi ed il Sigr. Benucci nell'Opera la Pastorella Nobile.")

- Ms. score in A Wn, K.T. 338 (A-Wn is the RISM siglum for Austria, Wien,

Nationalbibliothek, Musiksammlung. RISM stands for Receuil International

de Sources Musicales; there is a list of RISM sigla at the beginning of

every volume of the New Grove Dictionary of Music.

K.T. 388 is the call number (signature) of the manuscript; K.T. stands for Karntnertortheater, where the manuscript was kept before being transferred to the Nationalbibliothek).

- Published by Artaria in Vienna during the second half of 1790 (Racolti d'Arie No. 77)

- Duration: ca. 4'00"

- size 29 x 21 cm, 14 pages

Méthode de guitare pour apprendre seul à jouer de cet instrument, nouvelle édition, corrigée et augm[entée] de gammes dans tous les tons, des Folies d’Espagne avec leurs variations,….

- No published music found.

- Published in Fétis, François-Joseph, Biographie universelle des musiciens…, tome 2, 2e édition, Paris, 1866, p. 356

- Thanks to François-Emmanuel de Wasseige for detecting this item in literature

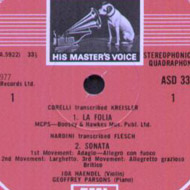

Opus V (Sonate a Violino e Violone o cimbalo) was first published in Rome on the 1st. January 1700, closely followed by publication in Bologna, Amsterdam (Estienne Roger) and London (John Walsh).

This work has remained a favorite among violinists because of the variety of technical challenges the variations offer to the player. They were extremely popular when they first appeared, and firmly established the composer's international reputation appearing in over a dozen different editions during Corelli's lifetime. Less than a hundred year after the first publishing, there had been at least 40 printings and more than 20 revised editions. Delphine Alard and Ferdinand David published performing editions in 1863 and 1867 respectively, but the arrangement by the Belgium violinist Hubert Léonard in 1877 firmly established the work as a mainstay in the repertoire of violinists. The arrangement for recorder was published in 1702 by Walsh & Hare of London as part of 'Six solos for a flute and bass'.

Geminiani who was a pupil of Corelli published a concerto grosso based upon Corelli's Op. 5 no. 12 and Veracini made his own arrangement for violin and basso continuo. Both composers introduced the Italian style in England. Vivaldi's Folia Op 1 no. 12 is another tribute to Corelli and the name Rachmaninoff gave to the title of his Folia ('on a theme of Corelli') leaves no doubt about his source for inspiration.

Marc Pincherle wrote about the Corelli-variations:

An effort to minimize inevitable monotony is discernible

in the set of 23 variations, particularly by giving to the accompaniment

as active a role as possible. Several times in the 3rd variation and in

the 16th the same designs are exchanged between melody and bass. Sometimes

this reciprocity operates between groups of two variations; for example,

between the 4th and 5th, 6th and 7th, 20th and 21st. Still more

revealing is the manner in which the ostinato of the bass is now and then

halted. The harmonic framework of the 14th is new, likewise that of the

19th, which is in imitation with supple modulations and that of the 20th,

which cadences in F while the 21st variation traverses the reversed key

sequence. Finally, an elongation by four measures at the close of the last

phase attests, by itself, to Corelli's desire to evade customary routine

and to invest a somewhat naive architecture with a degree of nobility.

But there is no doubt, as is evident from a cursory reading of the follia

that in Corelli's eyes its interest was of a violinistic order before all

else. Everything he knew about the matter of instrumental technique, which

he had scattered throughout Opus V, and the device of variation, enabled

him to concentrate, to classify, and to demonstrate with precision in a

veritable corpus of doctrine. By technique, that of bowing should be understood;

for as regards to the left hand, Corelli's role, (.....),

far from being constructive, was limited to 'pruning'.

|

Duration: 5'16", 40 kB. |

|

Duration: 7'03", 47 kB. |

|

Duration: 8'56", 59 kB. |

| Theme of Violin Sonata in d minor La Follia | arr. for violin and b.c. |

|---|---|

|

|

|

The complete score of la Folia opus 5 no. 12 |

- Accademia Bizantina directed by Ottavio Dantone 'Arcangelo Corelli, violin sonatas Opus 5'

- Title: Sonata No. 12 In Re Minore, 'Follia'

- Released November 2006 by Label: Blue Libe / The Orchard compact disc

- Duration: 11'02"

- Recording date: unknown

- Accademia Bizantina directed by Ottavio Dantone 'Arcangelo Corelli, sonate per violino e basso continuo Op. V'

- Title: Sonata No. 12 In Re Minore, 'Follia'

- Released 2003 by Amadeus compact disc 169-2 (2 cd-set)

- Duration: 11'05"

- Recording date: unknown

- Accardo, Salvatore (violin) Beltrami, Antonio (piano) 'Corelli, Porpora, Tartini, Vivaldi sonatas'

- Title: Sonata Op. 5 N. 12 in Re minore 'La Follia'

- Released by RCA original early 60's Italian pressing (promo white label) LP ML-80

- Duration: unknown

- Recording date: unknown

- Alard, Delphin and Meyer edited the music for viola and bassso continuo

- Title: Sonate d-Moll, op. 5/12

- Published by Schott

- Score 18 p.

- Publisher No. VAB8

- Ensemble Amarillis: Gaillard, Héloïse (recorder), Cochard,

Violaine (harpsichord), Gaillard, Ophélie (cello) 'Furioso ma non

troppo, Italie 1602-1717'

- Title: La Follia

- Released 1999 by Ambroisie compact disc AMB 9901

- Duration: unknown

- Recording date: August 1998 in la fondation Tibor Varga, Sion

- Angelloz, Guy (flute), Batselaere, Arnold (organ) 'Flute et orgue a

Notre-Dame de Paris'

- Title: Arcangelo Corelli: La Follia

- Released 1985(?) by Pierre Verany compact disc PV 785094

- Duration: 4'55" (booklet indicates 4'49")

- Recording date: April 10 & 11, 1985 in the Notre-Dame of Paris

- Anonymous transcription for large orchestra (c. 1802)

John A. Rice wrote about this transcription in 'Empress Marie Therese and Music at the Viennese Court, 1792-1807' page 67-68:

Marie Therese had at her disposal many wind and brass players, whom she sometimes brought together in orchestras that must have made a brilliant and colorful sound. Her concert on 18 July 1802 ended with what she referred to as "Die Follia di Spagna mit allen Instrumenten von Eybler." Eybler is not known to have composed such a work (footnote 66: No orchestral variations on La Follia by Eybler are listed in Hermann [= Hildegard Hermann, Thematisches Verzeignis der Werke von Joseph Eybler, Munich, 1976]). But she owned, under the title Follia a più strumenti, an anonymous orchestral transcription of the variations on La Follia from Corelli's violin sonatas, Op. 5 (CaM, p. 62; see Fig. 1.3), which the diary allows us to attribute to Eybler. The orchestral parts call for (in addition to strings) pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns, trumpets, and timpani (footnote 67: A-Wgm, XIII 29392).

- Title: Follia a più strumenti (or in the diary of Marie Therese: Die Follia di Spagna mit allen Instrumenten von Eybler

- Source: A-Wgm, XIII 29392 according to Pohl (Austria, Vienna, Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, call-number (signatur) XIII 29392

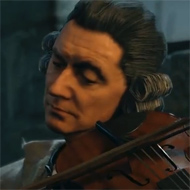

- Assassin's Creed Unity (video game)

Assassin's Creed Unity at 20'14" and further

Duration: 36'55" direct link to YouTube

© 2014 by Xari et Jiji

Le Lutin d'Ecouves wrote about the use of the Corelli Folia:

I had detected a little part of Corelli's Follia played with the solo violin in the Bastille in the video game "Assassin's Creed Unity (2014). Theme at 22:09 of this video and a variations at 23:35 to 26:53.

- Performer(s) unknown

- Title: Assassin's Creed Unity (video game)

- Released 2014

- Recording date:unknown

- Arita, Masahiro (flute), Bach-Mozart Ensemble Tokio 'Italian Baroque

flute music'

- Title: La Follia e-moll for traverse flute and basso continuo Op. 5 No. 12 (d klein)

- Released 1996 by Denon compact disc CO 18013

- Duration: 10'41"

- Recording date: January 20-23, 1996 in Akigawa Kiarara Hall, Tokyo, Japan

- L'Astrée ( Francesco D'Orazio violin, Alessandro Tampieri violin and baroque guitar, Alessandro Palmeri cello,

Francesco Romano theorbo, Giorgio Tabacco harpsichord)

- Title: Sonata "La Follia" per violino e basso continuo op.V n.12, Tema, Variazioni I - XXIII

- Broadcasted by RAI radio 3 (Italy) April 3 and October 30, 2005

- Duration: 10'24"

- Recording date: unknown at Cappella Paolina del Palazzo del Quirinale di Roma, Italy

- Autumn, Emilie (baroque violin) 'Laced, unlaced'

- Title: La Folia

- Released 2007 by Trisol Music Group 2 cd-set TRI 294

- Duration: 10'18"

- Recording date: unknown

- Autumn, Emilie (baroque violin) 'Laced, unlaced'

- Title: La Folia Live

- Released 2007 by Trisol Music Group 2 cd-set TRI 294

- Duration: 9'25"

- Recording date: unknown

- Balestracci, G.(viola da gamba), Pandolfo, P. (viola da gamba), Nassilo,

G (cello) Còntini, L. (arch lute) & Raschitti, M. (harpsichord)

'Arcangelo Corelli, Sonata per viola da gamba and basso continuo Opus

V, Vol II'

- Title: Follia

- Released 2002 by Symphonia compact disc 8 012783 011892

- Duration: 12'10"

- Recording date: October 2001 in Pieve di Tre Colli, Pisa, Italy

- Belder, P-J.(recorder), Schiffer, R. (baroque cello) & Stinder,

H. (harpsichord) '17th and 18th Century chambermusic'

- Title: Variationen über La Follia, opus 5, Nr. 12.

- Released 1992 by Erasmus compact disc WVH 058

- Duration: 11'04"

- Recording date: November 1991 in the Lutherse Kerk, Breda the Netherlands

- Belder, Pieter-Jan (recorder), Rainer Zipperling, Rainer (cello/viola da gamba) & Delft, Menno van

(harpsichord) 'The Art of the Recorder, Die Blockflöte - Pieter-Jan Belder'

- Title: 'La Follia' for recorder and basso continuo (opus 5 n.12)

- Released 2004 by Brilliant Classics compact disc 92460

- Duration: 11'01"

- Recording date: unknown

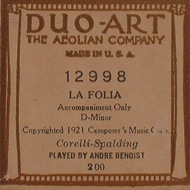

- Benoist, Andree 'Piano Roll: La Folia, accompaniment only'

piano roll, 1921

Click picture for magnification- Title: 'La folia in D minor' by Corelli in an arrangement by Spalding, accompaniment only

- Released 1921 by Duo Art, The Aeolian Company 12998, made in the USA

- Duration: unknown

- Recording date: unknown

- Besset, Serge and ensemble 'd'apres La Follia de Corelli'

See Besset, Serge (composers letter B)

- Bezverkhny, Mikhail (violin) 'Yuri Korchinsky and Mikhail Bezverkhny: Musical Tournament'

- Title: 'La folia'

- Released 1990 by Melodiya LP C90 29537 002

- Duration: unknown

- Recording date: 1988

- Bianchini, Chiara (Baroque violin), Darmstadt, Gerhat (Baroque cello), Gross, Alfred (harpsichord) 'Italian violin music 1600-1750'

- Title: La Folia op. 5/12

- Released 1986 by Edition Open Window Red-White, LP OW 002

- Duration: 10'50"

- Recording date: unknown

- Bobesco, Lola (violin) 'Lola Bobesco violin plays Bach and Mozart'

- Title: Sonata in Re Minor Op. 5 No. 5 (? instead of No. 12) 'La Follia'

- Released in the 1970's by Electrecord ( Romania ) White Label lp ECE 0844

- Duration: unknown

- Recording date: unknown

- Bohren, Sebastian (violin) 'La Folia'

In the slipcase was written by Tully Potter (Übersetzung Anne Schneider):

In the slipcase was written by Tully Potter (Übersetzung Anne Schneider):

Und wie könnte man die Stärken der Guadagnini besser demonstrieren mit diesem Album mit barocken Arrangements? Es geschah, als er einen YouTube-Clip von Ida Haendel sah, die Corellis La folia-Variationen (die 12. seiner Sonaten, op. 5) aufführte. „Sie spielte diese erstaunliche virtuose Kadenz. Ich fragte meinen Kollegen Daniel Kurganov, was das sei, und er meinte, die Kadenz stamme von Hubert Léonard.“ So entstand das Konzept eines ganzen Programms, das das Ethos von La folia widerspiegelt, das ohrenkitzelnde Thema, das Komponisten wie Lully, Corelli und Marais, Alessandro Scarlatti, Geminiani, Boccherini und sogar Rachmaninov fasziniert hat.

- Title: Violin Sonata in D minor Op.5 No.12 'La Folia'

- Released 2022 by AVIE 2513

- Duration: 11'28"

- Recording date: 2021

- Bova, Aldo (recorder) and Stolz, Ernst (organ )

Duration: 5'45" direct link to YouTube

The first part as played by Aldo Bova & Ernst Stolz

© 2009 Aldo Bova & Ernst Stolz, used with permissionDuration:6'26" direct link to YouTube

The second part as played by Aldo Bova & Ernst Stolz

© 2009 Aldo Bova & Ernst Stolz, used with permission- Title: La Follia by Arcangelo Corelli

- Published at YouTube August 2009

- A distance collaboration between the two musicians

- More about Ernst Stolz you can read at " http://www.ernststolz.com/ernststolz.htm

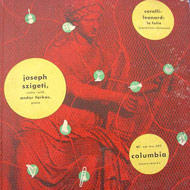

- Bratza, Milan (violin) and Vrederic Jacsicas (harpsichord) 'The historic Violin'

- Title: Sonata No 12 'La Follia'

- Released in 1930s Columbia Masterworks Music Appreciation 78 set. It is originally from Columbia's History of Music by Eye and Ear, Volume 3.

- Duration: unknown

- Recording date: 1930s

- Bress, Hyman (violin) 'The Violin: Vol. 1' (accompanied by the piano)

- Title: La Folia

- Released 1962 by Folkways Records LP FW03351, nowadays Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage

- Duration: 8'13"

- Recording date: not mentioned in the documentation

- Brink, Robert (violin) and Pinkham, Daniel (harpsichord) 'Arcangelo Corelli, sonatas for violin and harpsichord, opus 5 Volume 1'

In the documentation was stated:La Follia has proved the most popular and is the oldest permanent classic of the virtuoso's repertoire. It was a favorite with the 19th Century performers who added luxuriant accompaniments and spectacular cadenzas. In the original form, as recorded here, it consists of twenty-three variations for violin and harpsichord on the theme of an old Portuguese dance. The dance was originally accompanied by tambourines and performed by men dressed in women's clothes who acted so wildly that they appreared to be out of their senses, hence the title 'Follia' meaning 'Madness'

This tune was used in vocal music by Steffani and Milanuzzi. In harpsichord solo variations by d'Anglebert, François Couperin (Les Folies Françoises), Alessandro Scarlatti, and Pasquini. And in an organ setting by Cabanilles. J.S. Bach employed it in the ' Peasant Cantata' (record Allegro alg-82). It is found in works by Gretry (in the Opera 'L'Amant Jaloux') and in 'The Beggar's Opera' to the words ' Joy to Great Ceasar'. Other composers who made use of La Follia include François Farinel, whom Corelli met in Hannover around 1680, Lully, Frescobaldi, Marais, Pergolesi, Vivaldi, Keiser, Cherubini, Liszt, and even Rachmaninoff (in his Variations on a theme by Corelli, Opus 42).- Title: Variations on 'La Follia' (Sonata No. 12)

- Released in 1951 by Allegro LP AL 109

- Duration: 12'28"

- Recording date: January 1951 in Boston, USA

- Brüggen, Frans (recorder), Bylsma, Anner (cello) & Leonhardt,

Gustav (harpsichord) 'Italienische Blockflotensonaten um 1700'

Andrea Lausi wrote about recorder-music in general and in particular the Brüggen-Bylsma-Leonhardt-trio (used with permission, 2005):

I have always considered the anthologies issued by the Brüggen-Bylsma-Leonhard trio for Telefunken (Italian Recorder Sonatas, Blockflötenmusik auf Originalinstrumenten...) among the key recordings of the ‘70s. Veritable chamber music lesson, these recordings shaped the perception of the recorder as a musical instrument for many years to come. What I find central to this is the quality, so-to-say the real magic, of Brüggen’s sound. The recorder is an instrument with a particular limited amount of overtones – it is actually a good approximation to a sonic laser with all the energy concentrated in the fundamental – and Brüggen’s playing puts this quality at the center of his constant focus. A playing where the center of the tone is never missed, the sound being always direct and full. These qualities blend with the play of other two musicians in interpretations of a simple nobility, where the 'abstract' timbre of the recorder – the quality Brüggen once defined as its 'dangerous innocence' – appears perfectly functional in putting in evidence all of the curves and shapes of the compositional architecture.

The Brüggen-Bylsma-Leonhard series included also a very impressive rendition of the Follia and, given such an overwhelming example to confront with, I have been always surprised that in the past years so many recorder players recorded the piece, which after all is definitely not a piece composed originally for the recorder. [...] and I find the Cavasanti-Guerrero-Erdas reading to be perhaps the first to cope with the mastery of BBL example. [...]- Title: Variationen über La Follia, opus 5, Nr. 12.

- Released 1968 by Telefunken LP SAWT 9518-A Series: Das Alte Werk

- Recording date: February 1967, Bennebroek Holland

- Brüggen, Frans (recorder), Bylsma, Anner (cello) & Leonhardt,

Gustav (harpsichord) 'Italian recorder sonatas'

Ulrike Brenning wrote about La Follia as introduction for this recording:

Ulrike Brenning wrote about La Follia as introduction for this recording:

The work differs only in points of detail from the versions for violin and demands a high degree of technical competence on the part of its performance, since Corelli, an accomplished violinist, conceived the work as a virtuoso bravura showpiece. The folia or ostinato bass, after which the piece is named, is a solemn, weighty theme that is subjected to a total of twenty-one variations to produce a veritable fire-work display of ideas.

- Title: Variations on 'La Follia' Opus 5 No. 12 in G minor

for treble recorder and basso continuo from Sonatas by Arcangelo Corelli,

his V Opera London (Walsh) 1702.

- Released 1995 (prod. 1968) by Teldec compact disc 4509-93669-2 Series: Das Alte Werk

- Recording date: February 1967, Bennebroek Holland

- Duration: adagio 1'14" allegro 2'15" adagio 0'39" vivace 0'21" allegro 0'12" andante 0'30" allegro 0'41" adagio 1'25" allegro 2.49"

- Title: Variations on 'La Follia' Opus 5 No. 12 in G minor

for treble recorder and basso continuo from Sonatas by Arcangelo Corelli,

his V Opera London (Walsh) 1702.

- Brüggen, Frans (recorder), Bylsma, Anner (cello) & Leonhardt,

Gustav (harpsichord) 'Frans Brüggen Vol 2', Recorder works by 10 Italian composers

In the lp-box is written about La Follia as introduction for this recording:

In the lp-box is written about La Follia as introduction for this recording:

Corelli's variations on La Folia, from the beginning of the 18th century the composer's most famous work, were originally written for violin and figured bass and constitute, in this version, the last of the twelve 'Sonate a violino e violone o cimbalo', which first appeared in Rome with the superscription of 1st January 1700, and by 1720 saw no fewer than twenty reprintings, above all in Amsterdam and London.The present version for recorder (in which the only simplifications are of technical peculiarities like the chords or double-stopping of the violin version) had already been published in 1702 by Walsh in London. The imaginative title 'La Folia' (Walsh wrote 'La Follia') denotes nothing more than that the work is constructed on the bass pattern known as a 'folia', which first emerged in Spanish and Italian music in the early 16th century as a bass (i.e. as a harmonic framework) for vocal and instrumental movements, and thence, partly also combined with more or less fixed or varied upper melodic part, set out on its victorious path through Europe. In the instrumental music of Corelli's time, particularly in the sets of variations, this pattern atteined its richest flowering - not only Corelli himself, but also Pasquini, d'Anglebert, Cabanilles, Marais and Alessandro Scarlatti wrote sets of variations on La Folia, in so doing giving free rein to their imagination, particularly from the point of view of technique.

Corelli's 'sonata' is planned as a sequence of a theme and 21 variations. The theme preserves, along with the traditional 3/4 measure, the traditional descant melody and its sarabande character; thereafter movement and melodic figuration are increased from variation to variatio, and rhythm, tempo and compositional technique constantly changed, while the harmonic movement and its symmetric organisation (4 + 4, 4 + 4 bars, both halves repeated) remain firmly fixed. The frequent recurrence of long phrases building up from grave crotchet movement in sarabande rhythm to virtuosic semiquaver figurations in the separate movements gives the work its inner coherence and its accompanying dynamics; the abundance of ingenious melodic and constructional ideas and the extraordinary technical demands lend it that range of colour and that air of fantasy which already fascinated its contemporaries and made the work so uniquely famous.- Title: Variationen über 'La Follia' für Blockflöte in f' und B.c, op. 5, Nr. 12

- Released 1974 by Telefunken, Das alte Werk 3 lp-box 6.35073(-00-501)

- Duration: 10'10"

- Recording date: not mentioned in the documentation of the lp-set

- Alt-recorder in f', copy after P.I. Bressan built by Martin Skrowroneck, Bremen, Germany, 1966

- Brüggen, Frans (recorder), Bylsma, Anner (cello) & Leonhardt,

Gustav (harpsichord) 'Italian Recorder Sonatas'

- Title: Variations on 'La Follia' for recorder in F and continuo Opus 5 No. 12

- Released by Telefunken vinyl SAWT 9518-A EX, re-released 1994 by WEA/Elektra compact disc 4509 93669-2

- Duration: unknown

- Recording date: February 1967

- Brüggen, Frans (recorder), Bylsma, Anner (cello) & Leonhardt,

Gustav (harpsichord) 'Arcangelo Corelli, Sonatas Op. 5 No 7-12 La

Follia'

- Released by RCA SEON Red Seal LP RL 30393

- Duration: 9'30"

- Recording date: September 1979/March 1980 in De Lutherse Kerk, Haarlem

- Brüggen, Frans (recorder), Bylsma, Anner (cello) & Leonhardt,

Gustav (harpsichord) 'Arcangelo Corelli, Sonatas Op. 5 No 7-11 and No 12 La

Follia'

- Released 1990 by RCA SEON Red Seal compact disc

- Duration: 9'30"

- Recording date: September 1979/March 1980 in De Lutherse Kerk, Haarlem

- Brüggen, Frans (recorder), Bylsma, Anner (cello) & Leonhardt,

Gustav (harpsichord) 'Corelli's Sonatas Op. 5 No 7-12 La Follia'

- Released by RCA Victor Red Seal compact disc EURO RD 71055 (not available in North America).

- Duration: 9'30"

- Recording date: September 1979/March 1980 in De Lutherse Kerk, Haarlem

- Brüggen, Frans (recorder), Bylsma, Anner (cello) & Leonhardt,

Gustav (harpsichord) 'The art of the recorder'

- Title: La Follia, allegro

- Released 1995 by Teldec compact disc, Das Alte Werk 4509-99030-2

- Duration: 2'49"

- Brüggen, Frans (recorder), Bylsma, Anner (cello) & Leonhardt,

Gustav (harpsichord) 'Corelli, sonatas Op. 5, Nos 7-11, La Follia, Op.

5, No 12.'

Gustav (harpsichord) 'Corelli, sonatas Op. 5, Nos 7-11, La Follia, Op.

5, No 12.'

- Title: La Follia (in g minor)

- Released 1981 by Pro Arte lp PAL 1045, originally released

as Philips LP, and re-issued 1986 Pro Arte compact disc cdd 291 and

Sony compact disc.

- Duration: unknown but less than 9'30"

- Recording date: unknown but not after 1978

- Brüggen, Frans (recorder), Harnoncourt, Nikolaus (viola da gamba)

& Leonhardt, Gustav (harpsichord) 'Blockflötenwerke des Barock'

David Lasocki wrote about La Follia as introduction for this recording:

David Lasocki wrote about La Follia as introduction for this recording:

The final work in the collection is a set of 23 variations on La Follia, a sixteen-bar ground bass that had been used as the basis of variations for well over a century and had by then picked up an 'accompanying' melody in chaconne rhythm. This is something of a tour de force, particularly in bowing technique.

- Title: Variationen über La Follia für

Blockflöte (in f) und Basso continuo

1) Adagio 2) Allegro 3) Adagio 4) Vivace 5) Allegro 6) Andante 7) Allegro 8) Adagio-Allegro - Released by Telefunken LP SAWT 9560-M Series: Das Alte Werk

- Title: Variationen über La Follia für

Blockflöte (in f) und Basso continuo

- Brunello, Mario (cello) and Battiston, Ivano (accordeon) 'In croce'

- Title: La Folia (arrangement for cello and accordeon)

- Released 2001 by Velut Luna compact disc order number

- Duration: 9'18",

- Recording date: unknown

- Campoli, Alfredo (violin) and Gritton, Eric (piano) 'Alfredo Campoli plays Mendelssohn'

- Title: La Folia - Variations Serieuses

- Edition Hubert Leonard (with cadenza), revised by Issay Barmas, 3/-

- New release of old recording (78 rpm LP K1670-71), released 2002 by Dutton, compact disc CDBP 9718

- Duration: Part 1-4: theme and variations 3'15", Part 5-10: theme and variations 4'07", Cadenza: 4'15"

- Recording date: May 22, 1947 in Kingsway Hall, London

- Carolina Pro Musica 'Bridges from Europe to Peru'

- Title: La Folia, Opus 5 No. 12

- Released by Carolina Pro Musica

- Duration: unknown

- Recording date:February 11, 2001 at St. Martin's Episcopal Church, Charlotte, NC, a live concert recording

- Cartier, J.B. edited the music for violin and piano

- Published by H. Lemoine c.1911

- Score 13 p. and 1 part, 36 cm

- Series: Maitres italiens du violon au XVIIIe siecle, Edition J. Jongen et Joseph Debroux

- Cavasanti, Lorenzo (alt-flute in f), Guerrero, Jorge Alberto (cello), Erdas, Paola (harpsichord)

'Lo Specchio Ricomposto (the mirror recomposed)'

Gilles Cantagrel wrote for the slipcase: (translation by Christopher Cartwright and Godwin Stewart):

Duration: 0'54", 848 kB.( 128kB/s, 44100Hz)

The opening of Opus 5 nr. 12 as played by Cavasanti, Guerrero and Erdas

© Cavasanti, Guerrero and Erdas 2004, used with permission - Title: La Follia Op.5/12

- Released July 2004 by Stradivarius compact disc STR 33684

- Duration: 10'21"

- Recording date: August 8-10, 2002 in Montevarchi, Arezzo, Italy