|

Best recordings as introduction |

|

Thematical music is hardly recorded groupwise. So you have to buy all the other tracks as well just for that single Folia included. he only well-known exception for a long time was the Folia-recording of Gregorio Paniagua released back in 1982. This recording inspired modern Folia-composers because they refer to this recording or at least the approach of it as mentioned in the slipcase. Lately La Folia seems to gain popularity because from 1998 on there were more discs released completely devoted to Folias. A nice starting point for a concise discography as an introduction to the Folia theme for the interested reader not that familiar with the music itself.

The quality of performance is not that much taken into account, since this is rather arbitrary. For beginners the Folia-variations of Corelli (lead by violin) and Marais (lead by viola da gamba), both from the Baroque era, are recommended since they are generally considered to be the most famous Folias. For people interested in guitar music the disc of Luigi Attademo is recommended where all variations (47) are nicely indexed.

A detailed discography can be found in the chapter of composers (a-z).

|

Praetorius, Lisedore (harpsichord), Kussmaul, Rainer (violin), Wolf, Jurgen (viola da gamba and cello)

released c. 1950 (mono) total duration 43'37" |

Praetorius, Lisedore (harpsichord), Kussmaul, Rainer (violin), Wolf, Jurgen (viola da gamba and cello)

re-released 1967 (mono) total duration 43'37" |

This is the first compilation of later Folias as far as I know. A mixture of later Folias (C.P.E. Bach, Corelli, Marais) and two non-folias: the Frescobaldi (Partita sopra l'aria di Folia) which is despite the title a completely different dance namely the Fedele and the F. Couperin (Les Folies Françaises ou les Dominos). Unfortunately only half of all variations by Marais' Folies d'Espagne are played. No dates of recording-sessions or lp-release but I guess it can be dated around 1950 because the word 'stereo' was not invented yet but the performer Liselore Praetorius was teaching harpsichord at the Staatlichen Musikhochschule in Stuttgart from 1946 till the recording was released according to the text on the back of the LP.

Harmut Broszinski wrote for the backside of the cover of the Da Camera vinyl:

Der Titel "La Folia" wird heute wie

selbstverständlich mit der "berühmtesten aller

Sarabandenmelodien" identifiziert, doch gilt es einen kleinen Exkurs in

die Musikwissenschaft: wir wollen einmal der Entstehung des Namens, zum

anderen den Ursprüngen und der Entwicklung der Musik nachgehen,

die wir mit "La Folia" bezeichnen. Hiermit ist bereits angedeutet, dass

es sich um zwei verschiedene Dinge handelt. Zunächts zum Namen:

Seit dem frühen 15. Jh ist ein portugiesischer Tanz belegbar, der

anlässlich von Fruchtbarkeitszeremonien getanzt wurde. Nach heute

hat er seine Parallelen im Ritual des "Wilden Mannes" zu Basel, im

englischen "Morrisdance", auf den Balearen usf. In die höfische

Kultur des 14.-17. Jh. ging er als "Moresca" ein - eine sich u.a. in

Galliarden- und Giguenform bewegende Musik. Der alte portugiesische

Tanz der Morrisdance, und die Moresca hatten gemeinsam, dass

Männer in weiblicher Verkleidung, dass der "Morris" (Mohr), der

"fool" (Narr) oft hoch zu Ross, das will heissen auf den Schultern

ihrer Mittänzer, umhergetragen wurden. In Deutschland tanzte man

ihn nach den bekannten Melodien "Der schwarze Knab" (morris) und

"Narrenweis" (fool). Da sich jedoch die höfische Kultur inzwischen

von den Ursprüngen des Tanzes entfernt hatte, kam es zu

sonderbaren Missdeutungen. So ritt gelegentlich von Turnieren

("folla"), während die Banketthülle ("follia") mit

grünen Zweigen ("feuilles") geschmückt wurde, ein "morris"

auf einem Einhorn daher, das Rotwein ausschenkte. - Die mehr oder

weniger improvisierten Gesänge, die einen Teil dieser

Fruchtbarkeitszeremonien in Spanien und Portugal darstellten, drangen

in dramatische Schöpfungen des 15.-17. Jh. ein, so wie ja auch

eine Moresca am Schluss von Monteverdis "Orfeo" zu finden ist. Um 1500

taucht für diese Gesänge in Spanien der Name "folias" auf.

Was allerdings der Anlass zu dieser Namensgebung ist, ob die

"Narrheit", die "folla", die "follia" oder die "feuilles" (s.o.),

bleibe dahingestellt.

So wie dieser Tanz hat auch die Musik, die später den Namen

"Folia" übernahm, ihren Ursprung auf der Iberischen Halbinsel.

Zuerst lässt sie sich in einigen Stücken des "Cancionero de

Palacia" von Juan del Encina (1494) im Zusammenhang mit dramatischen

Werken, wenn auch zunächst in rudimentärer Form, nachweisen.

Wesentlich ist, dass weniger die "Melodie" als der Bass bzw. die

Harmoniefolge den Vorrang hat. Im Gegensatz zu der vollentwickelten

"klassischen" Form, die als Doppelzeile 16 Töne aufweist, bauen

fast alle dieser frühen Stücke auf einer 8-tönigen,

meist mit der Dominante endenden Bassstimme auf. Völlig fehlt noch

die rhythmische Bindung, es werden oftmals Mittelteile und

Wiederholungen einzelner Töne eingeschoben, wie es der text, zu

dem diese Musik geschrieben wurde, erforderte.

Auch in Italien lassen sie zu der Zeit ähnliche Formen nachweisen.

Der "Folia"-Bass hat enge Verwandtschaft mit Vertonungen von " terza

rima" - Texten der italienischen Gesellschaftsmusik und den ostinaten

Bassbildungen der Tänze "Romanesca" und "Passamezzo Antico", doch

sind diese, vielleicht in Anlehnung an die "Bassadanza" des 15.Jh.,

rhythmisch straff gebunden. Erst im frühen 17. Jh., nachdem sich

die Folia-Formel dem "Folia"-Tanz angepasst und dessen Namen

übernommen hatte, wird auch sie rhythmisiert. Wo sich "Romanesca"

und "Passamezzo" mit Vokalformen verbinden, wie in den englischen

"Ballad-tunes" oder etwa im "blues", sind auch sie zwar elastischer,

doch die "Folia" war seit eh und je der Gefahr des "Zersingens" mehr

ausgesetzt. Anlass dafür gaben wahrscheinlich die stereotyp sich

wie im Kreise drehende Musik, die förmlich nach Veränderung

schrie und die Assoziation Narrheit ("folie") - freies Spiel der

Phantasie.

Frescobaldi, der mit den "Riprese" seiner 6 Variationen noch dem

frühen Typus angehört, verwendet die Töne 9-16 des

Basses, variiert jedoch zwei von ihnen. Alessandro Scarlatti benutzt

nur die erste Zeile, die mit der Dominante endigt und baut auf ihnen 21

Variationen auf. Die endgültige "klassische" Form, doppelzeilig

und metrisch genau festgelegt, bildet sich allmählich bei den

grossen spanischen Gitarristen, wie Colonna, Sanseverino uns. im ersten

Viertel des 17. Jh. heraus. So kann Cervantes 1613 die "Folia" in einem

Atem mit der Ciaconna und der Sarabanda nennen.

In dieser Gitarrenliteratur kommt es weniger auf die genaue Fixierung

der "Melodie" an, da diese dem Spieler zur improvisation

überlassen wurde, als auf die Harmoniefolge, wabei der Bass oft

aus spieltechnischen Gründen variiert wurde.

Ihren Höhepunkt erreichten die "Folia"-Bearbeitungen Stücken

des Cancionero de Palacio" von Juan del Encina (1494) im Zusammenhang

schufen damals brillante Variationenketten für Tasten- und

Streichinstrumente. Couperin führte diese grosse Tradition fort,

indem er in seinem "Les Folies Françaises ou les Dominos" getreu

seiner brillanten Kleinkunst, die zwölf Couplets, die auf dem

16-tönigen Bass aufbauen, menschliche Eigenschaften, wie "La

Pudeur" oder "L'Ardeur" zeichnen lässt. Ph. E. Bachs

Variationenwerk beschliesst den Reigen der barocken

"Folia"-Bearbeitungen, doch bus zu Liszt (Spanische Rhapsodie, 1863)

und Rachmaninoff (1932) regt die unscheinbare Melodie die Komponisten

zu immer neuer Ausseinandersetzung mit ihrer zwingenden Magie an.

LA FOLIA: Variations on a popular melody by Frescobaldi—Couperin—Corelli—Marais—C.P.E.Bach.

The basis of traditional jazz is a traditional folk melody, upon which the musicians elaborate as the mood

takes them. In the negro jazz days of the nineteen-twenties, most of what are now known to have been the best

jazz improvisators could not read music anyway, and the folk tunes used as their basic melodies were passed on

by ear rather than by pen or print. Later on the jazz variations began to be written down, though they were

still based on well known folk melodies.

During the 17th and 18th Centuries, numerous compositions took the form of variations or sets of variations

on well known traditional melodies. The chorale variation was basically the same too, except that a hymn tune

rather than a popular melody served as the basis.

Perhaps the most well known Barock composition in the form of a popular tune, or Air & Variations, is the set

by J. S. Bach for the keyboard known as the Goldberg Variations (named after the dedicatee). The Air is played

'straight' at the outset, and is then followed by 30 variations on the Air, using every possible rhythmic and

contrapuntal device.

This record presents the Air and Variations idea in another form. LA FOLIA is a tune popular before and right

through the Barock age, it is supposed to have originated in Portugal in the 15th Century. Such was the

continued popularity, and such were the interesting harmonic possibilities of this tune, that a considerable

number of musicians wrote Variations using LA FOLIA as a basis. We have selected a number of these compositions

for this record, thus we present sets of Variations by five different composers from the early 1600's to the

mid-1700's, each using the tune LA FOLIA as the basis.

Not only does this afford a useful introduction to the art of Variation on a popular tune, the Barock

counterpart of traditional jazz, it is also interesting to follow the change in style from the early Barock

through to the early Classical of C.P.E.Bach. Nationally, Italy, France and Germany, with their own individual

styles, are represented.

- Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel (1714-1788)

- Title: Les Folies d'Espagne

- Performer: Praetorius, Lisedore (harpsichord),

- Duration: 9'05"

- Recording date: not mentioned

- Corelli, Arcangelo (1653-1713)

- Title: Sonate XII (La Follia) für Violine und Generalbass

- Performers: Praetorius, Lisedore (harpsichord), Kussmaul, Rainer (violin), Wolf, Jurgen (viola da gamba and cello)

- Duration: 12'27"

- Recording date: not mentioned

- Marais, Marin (1656-1728)

- Title: Couplets de Folies d'Espagne

- Performers: Praetorius, Lisedore (harpsichord), Wolf, Jurgen (viola da gamba and cello)

- Duration: 7'51"

- Recording date: not mentioned

Les Folies d'Espagne by Lisedore Praetorius

|

|

'La Folia de la Spagna' Gregorio Paniagua

reissue released unknown year ATR put out an earlier non-180 gram total duration 44'20" |

Gregorio Paniagua

HM 1050 released 1982 total duration 44'20" |

Gregorio Paniagua

(3 lp-set) reissue released total duration 44'20" |

Gregorio Paniagua

series Musique d'Abord released 2006 total duration 44'20" |

|

Japanese Vinyl Paniagua |

Fragment of this famous recording

|

La Folia is a disc with lots of relatively unknown early and later Folias in fantasy-arrangements including sitar, crumhorns and hurdy-gurdy. The Folias are crossed by harmony lessons of Hindou and fragments of Indian ragas. No familiar instrumentation for the Corelli or Marais, but all instruments are well played and the instrumentation occasionally gives a refined medieval flavour to the 'later' Folia theme which is unique compared to all other interpretations of the Folia-theme on other discs.

There is a huge difference between the documentation of the LP- and the cd-version. In both versions the history of the Folia as musical phenomenon is explained accurately but as the LP is a first class collectors-item because in a majestic table all the instruments and sources are explained and the recording quality is extremely high, the omission of this detailled table is rather painful in the slipcase of de cd-version because the sources are hard to identify in these fantasy-arrangements.

Here is the most important part for these pages of that table: the sources used for the arrangements of Paniagua.

LA FOLIA DE LA SPAGNA side A recorded

1980 |

|||

| Title of the Follias by Paniagua | Sources used as inspiration | ||

| 01 | FOLLIAS: | FONS VITAE | Atrium Musicae de Madrid. "Sunt lacrimae rerum et follias Hispanorum" |

| DEMENTIA PRAECOX ANGELORUM | Follias de Españia. Mss. Bibl. Nac. Madrid M 2810 (once variaciones). Anónimos. Musica para Salterio, Clave y Orquesta. folios 11, 12,13 y 14 | ||

| SUPRA SOLFAMIREVT | Atrium Musicae de Madrid et Leçon de solfège hindou, Benares. India | ||

| 02 | FOLLIAS | EXTRAVAGANS | Cuatro Folias anónimas. "Ramillete de flores" Bibl. Nac. Madrid Mss. 6001 folios 272, 273. Anno, 1593 |

| LAUREA MINIMA | Aquarelle de très petite dimension, exécutée avec une délicatesse particulière | ||

| FOLLIAS: IN VITRO | Rêverie fluorescente. Notre Dame des Anges. Lurs. Basses-Alpes | ||

| 03 | FOLLIAS | ORATIO PRO-FOLIA | Adorámoste Senor Iesuxristo. Fco. de la Torre. XVe sièc. Canc. Mus. de Palacio. Bibl. Real. Madrid |

| FAMA VOLAT | Indianapollis. Eau de source, chose qui se produit naturellement, du pétrole | ||

| CITRUS - HESPERIDES | Hermita de Nuestra Señiora del Pelotazo. Mar Caribe. Anc. fr. 99 la Valière | ||

| 04 | FOLLIAS: | PRINCIPALIS - FERMESCENS (Nihil ad me attinet) | "Huerto Ameno de varias flores de mússica" anno 1709. Obras recopiladas por Fray Antonio Martin Coll, Organista de S. Diego de Alcalá y de S. Francisco en Madrid. Bibl. Nac. Madrid Mss. 1360. "Las Folias" folios 212-215 |

| INDICA EXACTA | Raga : Yaman (Alap) Musique Classique traditionnelle hindoue | ||

| ADVERSO FLUMINE | Petite angoisse et anxiété antimusicologue. Oxygène & Ozone. 1980 Cercedilla | ||

| 05 | FOLLIAS: | PARSIMONIA ARISTOCRACIAE | Libro de Musica de Clavicimbalo del Sr. Dn. Francisco de Tejada. Sevilla 1721 Mss. 815. fols. 72-73. Madrid Bibl. Nac. "Folias graves" |

| Ministère des travaux publics. Ramassage de coquelicots. France | |||

LA FOLIA DE LA SPAGNA side B recorded

1981 |

|||

| Title of the Follias by Paniagua | Sources used as inspiration | ||

| 01 | FOLLIAS: | SUBTILIS | Jean-Francois Pontefract. harmonia mundi, 04870 Saint-Michel de Provence |

| DE PROFUNDIS - EXTRA MUROS | Cancionero Sephardita "Judeo-Espaflol traditional : El rey por muntha madruga" | ||

| 02 | FOLLIAS: | VULGARIS - SINE POPULI NOTIONE | Folias de España. Gaspar Sanz. Instruccion de Musica. Caesaraugusta 1674 |

| VAGULA ET BLANDULA | Nuit d'Espagne pendant laquelle on ne dort pas. Toledo XVe siècle | ||

| 03 | FOLLIAS: | NORDICA ET DESOLATA | Variations "d'après la Folia : Doen Daphne d'Over schoone maeght" Jr. Jacob van Eyck. "Der fluyten lust hoff" Amsterdam 1646 |

| AUREA MEDIOCRITAS | Improvisatione ad mente : Country dance XVIIIe siècle d'après John Playford. London "The englishdancing master" anno 1651 | ||

| 04 | FOLLIAS: | NOBILISSIMA | Bernardo Pasquini (1637-1710), Partite sopra la aria della Folia da Espagna |

| DEGRADANS ET CORRUPTAE | Cajita de Musica desafinada. El Rastro. Madrid vers 1850 | ||

| 05 | FOLLIAS: | DE PASTORIBUS | Folia "Rodrigo Martines" Anónimo. XVe s. Canc. Mus. de Palacio no 12. Bibl. Real. Madrid |

| MATHEMATICA DIES IRAE | Sequentia "Missa pro defunctis" atrib. Tomas de Celano. Liber usualis | ||

| CREPUSCULARIS | "Muchos van de amor heridos" Anónimo. Canc. Mus. de Palacio no 92. Bibl. Real. Madrid | ||

| SINE NOMINE | Improvisatio ad libitum. "Notre Dame des Angles immortelles" | ||

| TRISTIS EST ANIMA MEA | "Dime triste coracon" folia. Francisco de la Torre. Can. Bibl. Colombina Sevilla XVe s. | ||

| EQUITES FORTIS ARMATURAE | "Sefiora de fermosura" folia. Juan dell Enzina. Canc. Mus. Palacio no 81 Bibl. Real. | ||

| AUDACES FORTUNA JUVAT | "Pues que ya nunca os veis" Juan dell Enzina. Canc. Mus. Placio no 271 Bibl. Real. | ||

| SINE PRAEPUTIUM | Improvisation sur un thème de Jazz : La Boussole et rose des vents | ||

| ECCLESIASTICA | Fabordon "Arte de taner Fantasia" Fray Thomas de Sta. Maria Madrid 1565 | ||

| 06 | FOLLIAS: | THEATRALIS ET HIPOCRITAE | Folies d'Espagne. Bethune le Cadet. M. Monien. Pièces en tablature d'angélique. Paris 1681 |

| RURALIS | Country dance "La nouveauté a toujours un charme particulier" | ||

| ALTER INDICA PERFECTA | Raga : Yaman. Musique classique traditionnelle hindove. Benares 1979 | ||

| 07 | FOLLIAS | DE TOLERENTIA AETHEREA | Adagio "La Follia" Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713) op. 5 no 12. PubI. pour flûte douce : John Walsh. London 1702 |

| FUGA FICTA ET CARRUS TRIUMPHALIS | Sonata "Carrioches" dedicada al Exemo. Alcalde de S. Ildefonso de la Granja : Sr. Dr. Erik Claveria. Agosto de 1979. Rosalia's Follia's . Archivo particular de Gregorio Paniagua & Beatriz Amo | ||

Below is the list of sources Paniagua didn't use for his recording which gives a lot of information about Folias and which is no part of the slipcase version of the compact disc:

SOURCES NON UTILISEES

"Honce Diferencias de Folias" Mendoza. Mss. 6001 Bibl. Nac. Madrid.

Ramillete de Flores, 1593 - Choreografie, M. Feuillet, Paris 1700. Folie d'Espagne

pour femme. Bibl. Nac. Madrid M 1146/2 - Folias de España. Bibl. Nac.

Madrid. M 1884 - Folias no 22 Arte de Danzar. Pablo Minguet e Yrol (1758). Bibl.

Nac. Madrid. R. 14649 - A. Corelli. Sonata La Follia. Violin y Clave. Opus 5

no 12 - Folias "Poema Harmonico". Francisco Guerau, Madrid 1694. Fol.

51 - Folias "Pensil deleitoso de suabes flores de Musica" Fray A.

Martin Coll. Alcalá de Henares 1707, Mss. B. Nac. no 1358 - Folias "Flores

de Música" Fray A. M. Coll, Alcalá 1708. B.N. Mss. 1359 -

Otras Folias. "Huerto ameno" Fray A.M. Coll, Alcalá 1709. B.N.

Madrid Mss. 1360. Fols 215 v - 217 - "Libro de Cifra Nueva para tecla,

harpa y vihuela" Luys Venegas de Henestrosa, Alcalá de Henares,

1557. Duo "Pues no me quereis hablar" Anon. & "Para quien

crie yo cabellos ?" Antonio de Cabezon - Cancionero Musical de Palacio,

Siglos XV-XVI, Madrid Bibl. Real. sign. 2-1-5 : no 310 : "Meu naranjedo

no ten fruta" Anón. & no 361 : "No puedo apartarme"

Anón. & no 179 : "Si abrá en este baldres" Juan

dell Enzina (1469-1529?) - Ensalada "La Trulla" Cáceres. Bibl.

Central Barcelona M. 588 - "Goigs de Sant Cristófol" Folia

a 4. Mss. siglo XVI. Ayunt. Valencia, texto en catalan anno 1449 - "Tonos

Humanos" B. Nac. Madrid Mss. 1261. Chacona, Folia & Xacara - Folia.

Jácara, para clave. B.N. Madrid, Mss. 1357 - Del grupo de Folias vocales

derivan : Pavanas 1 y II. A. Mudarra "Musica para Vihuela" Sevilla

1546. Folia-sPavanas de E. Valderrábano "Silva de Sirenas"

Valladolid 1547. Pavana, Diego Pisador, Salamanca 1552. (Folia). "Pavana

con su glosa" A. de Cabezón "Libro de Cifra Nueva" Alcalá

de Henares, 1557 - Follias en "Las Ensaladas" Mateo Flecha (1481-1553).

Praha 1581. "Para mi lo querria madre mia" (EI Jubilate). "Venid

presto pecadores" y "Alegria Cavalleros" (El Fuego) - Otras "Follias

d'Espagne" en Bibl. Nac. Madrid M. 811, M. 815, M. 1358, M. 2262, M. 2801

- Follias, Arpa y Guit. "Luz y Norte para caminar por las cifras de la

guitarra españiola" Lucas Ruiz de Ribayas. Añio 1677 - Follias

di Spagna "Sonate di Chitarra Spagnola" A. Carbonchi Fiorentino. B.N.

Madrid M. 3785, Anno 1640 - "La guitarre Royale" de Francisque Corbett.

"Folias d'Espagne". Paris 1671 - Folia di Spagna. L'accademico Coliginoso.

"II Foscarino" "I quatro Libri della Chitarra Spañola"

S. XVII - "Folias mui despacio al estilo de Francia" Santiago de Murcia,

"Resumen de acompañar la parte" Madrid 1714, B. Nac. R. 5048

- Recercadas VII y VIII sobre La Follia. Diego Ortiz Tolledano. "Tratado

de Glosas sobre Clausulas" Roma 1553 - Diferencias de Folias. Iohannis

Cabanilles. Mss, de fines del Siglo XVII, B2. Barcelona. Bibl. de Cataluñia

M. 387 (888). B3. Barna, B. de C. M. 729 (980) - "Folias con 20 diferencias"

Jose Ximenez, S. XVII. Corpus of Early Keyboard Musik. W. Apel & "Antología

de Org. Espanoles" H. Anglés - Tema de Folias, Folias de Santander,

etc. en "Canc. Mus. Pop. Español" Felipe Pedrell. Barcelona

Ed. Boileau 1958 - Folia : "En la cumbre, Madre" Juan Pujol &

Folia : "Cervatilla que corres" Juan Arañes, Canc. Bibl. Canatense.

Siglo XVII - "Les Folies d'Espagne". Tablature pour le Luth (a due

Liuti) Köln 18 Jahrhundert - Folia-Romanesca "Guardame las vacas"

M. Flecha. "La Viuda" S. XVI-XVII - Folia "Si una volta"

Canc. de Olot. Popular-Catalonya, vers 1650 - A. Moser : "Zur Genesis de

Folies d'Espagne", in Af. M. w.I, 1918-19 - O. Gombosi. "Zur Frühgesels

des Folies", in A.M.I. VIII, 1936 - O. Gombosi. "The Cultural and

Folkloristic Background of the Folia" in Papers of the "American Musicological

Society". IV. 194 et. - Works sopra "La Folie d'Espagne" de P.

Nettl "Die Musikgeschichte des Tanzes" 1945 & Opus, J. Ward -

"La Folia historica y la Folia popular canaria" Rev. EI Museo Canario,

Las Palmas 1965 - "La tradicion coral hispánica de la '`Folie d'Espagne"

y sus derivaciones instrumentales" M. Querol. Anuario Mus. Vol. XXI, Barcelona

1968 - "De Musica Libri Septem" Fco. Salinas. Salamanca 1577 - Canc.

de la Sablonara S. XVII - Folia, Jakuba Duran Loriga. Madrid 1980 - "Folias

de España" par: G. Stefani (1622), C. Milanuzzi, Marin Marais, A. Corelli,

d'Anglebert, J.B. Lully, G. Frescobaldi, F. Farinelli, Manetti, A. Vivaldi,

Keiser, Pergolesi, C.P.E. Bach, J.S. Bach, Gétry, Cherubini (L'Hôtellerie

portugaise), Liszt (Rapsodia Española 1863), G. Fauré, C. Nielsen (Mascarade,

1906), Rachmaninov... et cetera.

In 1982 Gregorio Paniagua wrote for the slipcase (only the text in regard to the later Folia is quoted):

At the beginning of the 17th century the dance was

fashionable throughout Europe and, perhaps by being transformed into a

kind of passacaglia or 'ground' which gave it a quiet and even a severe

style, it lost its rapid tempo and its original orgaistic vitality.

This mutation served as the pretext for certain pedants and sages to

attribute to the Folia a different origin than its Hispanic one and to

use it as a basis for their theories on the basso continuo and its

Italian origins.

Nonetheless, all European musicians designated these dances as 'Folies

d'Espagne'. It should be borne in mind that all the time the term

'España' referred to all the countries in the Iberian Peninsula.

Thus we have 'Folies d'Espagne' by G. Stefani (1622), C. Milanuzii,

Corelli, d'Anglebert, Lully, Frescobaldi,

Michel Farinel (Farinelli or Faronel) - who introduced them into

England -, Manetti, Vivaldi, Keiser,

Pergolesi, Johann Sebastian and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach,

Gréty. Cherubini quoted Corelli's piece in the ouverture to his

L'Hôtellerie Portuggaise' (1798), and the Danish composer, Carl

Nielsen used the theme in his opera 'Maskerade' (1905). Liszt included

it in his 'Rhapsodie Espagnole' (1863).

All the composers in the world who write their own Folia don't keep a

close account of what they are doing. They mature patiently like the

tree that does not haste his sap; They soak up everything and remain

confident in the torments of spring, without anxiety that they might

not know another spring. And spring comes and and a quiet weariness

overcomes them, even if all eternity lay before them.

They can then love their Folia and their solitude; they endure the pain

it causes them and succeed in investing the sound of their complaint

with beauty.

'Klavier Variations on La Follia'

James Bonn

|

released 1982

total duration 46'05"

This is a noteworthy release in more than one way. It was released before the Folia-theme became very popular as a central theme for a recording (the late 1990's and later), the documentation of Maurice Hinson is extremely good and best of all is that four different keyboards are used to give the performances an historical setting. I can imagine that it demands extra technical capabilities of the performer besides the organization of the different instruments for a recording-session, but the results were well worth the effort. You can easily compare the different instruments in their musical setting and the treatment of the Folia-theme within that context, although the performer might not be a virtuoso on all four different instruments. But somehow that disadvantage feels not that important anymore.

Maurice Hinson wrote for the slipcase about the Folia-theme in general (see for his excellent characteristics of the individual pieces at the pages of the composers):

This recording follows the use of the folia, a famous melody of the 17th century, by four composers from four different centuries:

Bernardo Pasquini (1637-1716), C.P.E. Bach (1714-1788), Franz Liszt (1811-1886), and Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873?1943). The folia (follia, follia di Spagna, folies

d'Espagne) was originally an ancient Portuguese dance. Melodies titled folia are on record as early as 1577, and it is upon the bass of one of these

tunes that most folia variations are constructed. Paul Nettl, in his article "Zwei spanische Ostinato?themen", Zeitschrift für Musikwissenschaft, I

(1918-1919), 694-698, shows the appearance of the folia theme still earlier in the lute books of the middle 16th century, but these themes were not specifically

named folies. Some folias, like Alessandro Scarlatti's Variazioni sulla follia di Spagna, utilize only the first half of the bass.

That work includes twenty-nine variations and often involves very noteworthy and original formulae. Other sets are built upon the melody,

as well as the bass, of this ancient dance, but such sets, examples of melodic-harmonic treatment, cannot be regarded as true basso ostinato variations.

The twelfth violin sonata of Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713) is one of the most celebrated of all folias and is of this type.

Rachmaninoff used this folia in his op.42 "Corelli" Variations.

The Variations sur les folies d'Espagne by Jean Henri d'Anglebert (1628-1691) is the earliest example of the song variation in

France, perhaps the only one except for 18th-century noels. Most of its twenty-two variations remain within the limits of the French style, but a few are

composed according to the formula variation recipe, which d'Anglebert probably received from Italy.

- Bach, Carl

Philippe Emanuel (1714-1788)

Folie d'Espagne performed by James Bonn

Duration: 8'48" direct link to YouTube

© 1982 by James Bonn- Title: 12 Variations auf die Folie d'Espagne (1778)

- Performer: James Bonn (Dulcken fortepiano)

- Duration: 8'48"

- Recording date: not mentioned in the documention

- Liszt, Franz

(1811-1886)

Rhapsody Espagnole performed by James Bonn

Duration: 8'42" direct link to YouTube

© 1982 by James Bonn- Title: Rhapsody Espagnole (1867)

- Performer: James Bonn (Erard piano)

- Duration: 13'12"

- Recording date: not mentioned in the documentation

- Pasquini, Bernardo (1637-1710)

Partite di Follia by James Bonn

Duration: 5'00" direct link to YouTube

© 1982 by James Bonn- Title: Partite di Follia (c.1697)

- Performer: James Bonn (Flemish harpsichord)

- Duration: 5'00"

- Recording date: not mentioned in the documention

- Rachmaninoff,

Sergei (1873-1943)

Variations on a Theme of Corelli by James Bonn

Duration: 19'05" direct link to YouTube

© 1982 by James Bonn- Title: Variations on a Theme of Corelli (1932)

- Performer: James Bonn (Bosendorfer piano)

- Duration: 19'05"

- Recording date: not mentioned in the documentation

'La Folia'

Werner Bärtschi

|

released 1983

total duration 48'39"

In 1982 Werner Bärtschi wrote for the slipcase about the Folia-theme:

Die Folia ist ein alter, ursprünglich

portugiesischer Tanz, der durch eine feststehende, in einer einfachen

Bassformel repräsentierte Harmoniefolge charakterisiert wird. Die

darüberliegende Melodie folgte ursprünglich zwar einer

gewissen Grundstruktur, war aber im einzelnen frei, bis Arcangelo

Corelli eine besonders einsprägsame melodische Formuliering der

Folia zum Thema seiner Violinvariationen machte. Der Erfolg seines

Werkes bewirkte, dass vom 18.Jahrhundert an unter Folia normalerweise

diese (ursprünglich nicht von Corelli stammende) Melodie

verstanden wird. Sie representiert bereits den Typus der

'Themenmelodie' im klassisch-romantischen Sinne und kann in ihrer

zweizeiligen Gestalt mit offenem Dominantklang am Ende der ersten,

abschliessender Tonika am Ende der zweiten Zeife

als inbegriff eines Themas schlechthin gelten.

Diese Eigenart hat ihr zu einem überraschenden Nachleben

verholfen, denn im gleichen Masse, wie die Folia

durch ihre melodische Erstarrung fur den alten, auf der Wiederholung

von Bass und Harmoniefolge beruhenden

Variationstypus ausser Betracht fiel, bot sie sich dem neunen, am

thematischen Denken orientierten Komponieren als ideale

Variationsgrundlage an. Die jüngeren drei der vier aud dieser

Schallplatte vereinigten Werke sind die gewichtigsten Beispiele dieser

posthumen Karriere der Folia. Ist es ein Zufall, dass sie alle in den

letzten Lebensjahren ihrer Verfasser enstanden sind?

- Bach, Carl

Philippe Emanuel (1714-1788)

- Title: 12 Variationen auf die Folie d'Espagne (1778)

- Performer: Werner Bärtschi (piano)

- Duration: 8'18"

- Recording date: February 2nd in Thun Switserland, 1982

- Liszt, Franz

(1811-1886)

- Title: Rhapsodie espagnole (1867)

- Performer: Werner Bärtschi (piano)

- Duration: 13'47"

- Recording date: February 2nd in Thun Switserland, 1982

- Rachmaninoff,

Sergei (1873-1943)

- Title: Variationen für Klavier über ein Thema von Corelli (1932)

- Performer: Werner Bärtschi (piano)

- Duration: 18'41"

- Recording date: February 2nd in Thun Switserland, 1982

- Scarlatti,

Alessandro (1660-1725)

- Title: Folia (1715)

- Performer: Werner Bärtschi (piano)

- Duration: 7'44"

- Recording date: February 2nd in Thun Switserland, 1982

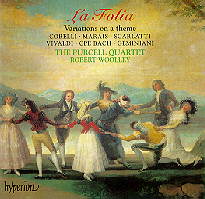

Various artists

|

released February 1998

total duration 68'22"

A virtuoso performance of all Folias in a rather sober style unlike for instance the Vivaldi-performance of Il Giardino Armonico or the C.P.E. Bach-interpretation of Rafael Puyana. A nice opportunity to focus entirely on the comparison of the compositions, not distracted by different musicians, instruments or musical interpretations. When you are interested in all the introducing Baroque highlights of the 'later' Folia, this recording is highly recommended.

- Bach, Carl

Philipp Emanuel (1714-1788)

Robert Woolley plays all variations by C.P.E. Bach

Duration: 7'56" direct link to YouTube

© 1986 by Robert Woolley- Title: Variationen über die Folie d'Espagne, Wq118/9/H263 (1778)

- Performer: Robert Woolley (harpsichord solo)

- Duration: 7'56"

- Recording date: October 29/30, 1986

- Corelli,

Arcangelo (1653-1713)

The Purcell Quartet plays all variations by Arcangelo Corelli

Duration: 9'56" direct link to YouTube

© 1986 by The Purcell Quartet- Title: Sonata in D minor, Op. 5 No 12 (1700)

- Performers: Elizabeth Wallfisch (violin), Richard Boothby (cello), Robert Woolley (harpsichord)

- Duration: 9'56"

- Recording date: May 22-23, 1986 in St. Barnabas's Church, London

- Geminiani,

Francesco (1687-1762)

The Purcell Quartet plays all variations by Francesco Geminiani

Duration: 10'52" direct link to YouTube

© 1987 by The Purcell Quartet- Title: Concerto Grosso 'La Folia' (after Corelli) (1726)

- Performers: The Purcell Quartet: Catherine Mackintosh (violin), Elizabeth Wallfisch (violin), Richard Boothby (cello), Robert Woolley (harpsichord) and the Purcell Band: Pavlo Beznosiuk (violin I), Catherine Weiss (violin I), Henrietta Wayne (violin II), Francis Turner (violin II), Alan George (viola), Barry Guy (violone), Lucy Carolan (organ).

- Duration: 10'52"

- Recording date: June 4/5 and/or 12, 1987

- Marais, Marin

(1656-1728)

The Purcell Quartet plays all variations by Marin Marais

Duration: 16'22" direct link to YouTube

© 1988 by The Purcell Quartet- Title: Les Folies d'Espagne (1701)

- Performers: The Purcell Quartet: Catherine Mackintosh (violin), Elizabeth Wallfisch (violin), Richard Boothby (cello), Robert Woolley (harpsichord) with William Hunt (viola da gamba)

- Duration: 16'22"

- Recording date: May 1988 in the Church of St. Peter and All Saints, Petersham

- Scarlatti,

Alessandro (1660-1725)

Robert Woolley plays A. Scarlatti 's Folia as part of the Ottava stesa

Duration: 13'12" direct link to YouTube

© 1987 by The Purcell Quartet- Title: Folia from Toccata No 7 (Primo tono) from the Primo e Secondo Libro di Toccate (1715)

- Performer: Robert Woolley (harpsichord solo)

- Duration: 13'04"

- Recording date: April 1987

- Vivaldi,

Antonio (1678-1741)

The Purcell Quartet plays all variations by Antonio Vivaldi

Duration: 9'28" direct link to YouTube

© 1985 by The Purcell Quartet- Title: Trio Sonata in D minor (Variations on 'La Folia') RV63 (Op I No 12) (1705)

- Performers: The Purcell Quartet: Catherine Mackintosh (violin), Elizabeth Wallfisch (violin), Richard Boothby (cello), Robert Woolley (harpsichord) with William Hunt (viola da gamba)

- Duration: 9'28"

- Recording date: September 1985

Ruggero Laganà

|

released August 2010

total duration 79'26"

If you are fond of the harpsichord as an instrument and of Folïas this disc is a must have! The only thing lacking is good references of the sources but there are absolutely no weaknesses on this fabulous disc to be found. If you think that so many folías will be monotomous and boring,which might be hard to avoid, I can assure you that Laganá is no metronomic automat but he has all the skills and knowledge about the pieces to paint a full indepth landscape.

This is not the first Folía-encounter for Ruggero who has corporated with the Amadeus-project and recorded previously the Alessandro Scarlatti's Folías variations, he also played at live recitals. For this disc he recorded the full Ottava Stesa including the wonderful parts which preceed the Folía-piece. Other compositions he previously recorded are the manuscript published by Martín Y Coll and the Pasquini Folías. So Laganà is in familiar territorium.

With the Follia di Spagna by Johann Baptist Cramer he had a première on the Amadeus disc, and there is another Folía premiere on this disc with "The Spanish Follye" I only heard once played on the organ by the late Ewald Kooyman although the piece is rather prominent mentioned in the study by Richard Hudson.

Not all pieces on this recording represents Folías. The central theme of the recording is Folías and the similar music from the region of Naples and Rome. Frescobaldi, Majone and Trabaci are represented with closely related Fidele as an arch type of music.

More about the disc at Concertoclassics http://www.concertoclassics.it/catalogo_dettagli.php?codice=31&pagina=2&dove=catalogo.php

.In music, the form foolia refers to a melodic pattern derived from a very old Carnevale dance - one of those restless, frenetic, impetuous dances in which everyone loses his head and every body loses its composure. Perhaps as Francisco de Salinas, the magister of the the University of Salamanca said in the 16th century, it originated in Portugal and, spreading quickly throughout the Iberian Peninsula, it immediateley became established in Europe. It appeared in the court music of the great 16th century virtuosos - as solo dances or in pairs.

Take for example the fascinating variations elaborated by Marin Marais for the viola da gamba. Later in the 17th century, it surfaced among the Arcadians, contributing to the definition of Arcangelo Corelli's violin style. It continued spreading throughout Germany among the pianists of the 18th century ... and we could carry on right up until today.

Leaving its Lusitanian origins, the so called Follia di Spagna became particulary successful thanks to its melody and the native simplicity of its harmony, as can be clearly heard in the many anonymous folía taken from collections dating to the early 1700's by the Biblioteca Nacional in Madrid. Organists and harpsichordists of various nationalities have been inspired by the Folia, but this CD focuses on its use in Italian music, in particular, from the Rome and Naples.

- Anonymous (c.1685 )

- Title: The Spanish Follye (1685)

- Duration: 2'06"

- Recording date: October 2009 Bartok Studio, Bernareggio (Mi), Italy

- Anonymous (1721)

- Title: Folias graves (1721)

- Duration: 2'09"

- Recording date: October 2009 Bartok Studio, Bernareggio (Mi), Italy

- .. (1956- )

- Title: Folia Folle (2008)

- Duration: 9'29"

- Recording date: October 2009 Bartok Studio, Bernareggio (Mi), Italy

- .. (1964- )

- Title: A Devil Behind the Mask (2008)

- Duration: 8'56"

- Recording date: October 2009 Bartok Studio, Bernareggio (Mi), Italy

- Martín y Coll, Antonio

(1709)

- Title: Las Folías

- Duration: 3'47"

- Recording date: October 2009 Bartok Studio, Bernareggio (Mi), Italy

- Pasquini, Bernardo (1637-1710)

- Title: Partite diversi di Follia

- Duration: 6'39"

- Recording date: October 2009 Bartok Studio, Bernareggio (Mi), Italy

- Pasquini, Bernardo (1637-1710)

- Title: Partite sopra la Aria della Folia de Espagna

- Duration: 1'35"

- Recording date: October 2009 Bartok Studio, Bernareggio (Mi), Italy

- Scarlatti, Alessandro (1660-1725)

- Title: Toccata per cembalo d'Ottava stesa (1723) (with), Variazioni sulla Follia di Spagna

- Duration: 18'52"

- Recording date: October 2009 Bartok Studio, Bernareggio (Mi), Italy

Anders Borbye

|

released October 2008

total duration 65'11"

Modern guitar music has the academical imago that it is artificial and therefore hardly accessible for ordinary listeners interested in serious tonal music. I guess that Anders Borbye had this prejudice in mind when he started this project to give it a fresh yet modern approach. Fascinated by the Folia theme he tried to extend the oeuvre into the 21st century by highlighting accessible yet startling modern guitar-Folias. Best of all he persuaded three Danish composers to write new Folia-compositions for his project which resulted in a well varied compact disc entirely devoted to the Folia-theme as a starting point. The demanding journey not only demonstrates a wide variety of guitar techniques ranging from tapping on the body of the guitar to bottleneck technique and an electric performance with flanger but also it shows the inventiveness of composers and the performer to handle such a small theme as the Folia because the theme is actually never far away.

Although the Folia-theme itself is exposed several times (for instance in the ending of Izarra's en Gunge's compositions) perhaps it would have been appropriate to play the bare theme as opening track just once as a statement for people not familiar with the theme.

Personally I consider the performance of Izarra's 'Lenta' (5'08") as the absolute highlight of the cd. Not only because it is played with flair very 'slowly' and vulnerable as an open nerve but probably these moments of reflections are even emphasized by the squeezed up-tempo pieces of the suite.

Although the pieces are all demanding the sound of all tracks is clear and there is never a moment where muffling of strings is to be heard in any way. The documentation of the disc is excellent. A project that gives new and fresh impulses to a very old idea.

More about Anders Borbye at http://www.andersborbye.dk

The idea with this CD is to present a programme of new music, which is uncomplicated and rewarding to listen to, even for people not familiar with such music. This is achieved by basing the music on a well known and quite simple melody, namely the Folia theme.

This theme has gone with me ever since the music school. It has in its basic form an inner cohesion which strongly appeals to my need for logic, purity and stringency. The guitar literture has some great works based on the folias, Sor, Giuliani and in the 20th century Ponce and Ohana. So I decided that the pieces on the CD should not be older than 30 years, which is just true with Malipiero. I wanted to have one world premier on the CD, but to my surprise 3 out of 4 composers I asked immediately said yes, and there I was with 3 world premiers!

Given the simplicity of the theme I am genuinely impressed with the creativity and fantasy shown by the composers, when theywork within this strict frame!

Judging from the history of music I am not the only one who has been fascinated by la Folia. There are hundreds of compositions based on the Folia theme, a lot of them for the guitar.

Three well known Danish composers, John Frandsen, Peter Bruun and Bo Gunge have written especially for this project. The other works on this CD were selected from a large number collected from all over the world. All composers involved have been very obliging, and have kindly contributed the notes for their works

- Bruun, Peter (1968- )

Duration: 1'00", 941 kB. (128kB/s, 44100Hz)

Fragment of Refolia, performance by Anders Borbye

© 2008 Anders Borbye, used with permission- Title: Refolia (2008)

- Duration: 6'15"

- Recording date: August-September 2008 in the Frederikskirken, Aarhus, Denmark

- World première

- Campo, Regis (1968- )

- Title: Sonate la Follia (1998)

- Duration: 3'28"

- Recording date: August-September 2008 in the Frederikskirken, Aarhus, Denmark

- Frandsen, John (1956- )

Duration: 0'43",651 kB. (128kB/s, 44100Hz)

Fragment of Folia Folle, performance by Anders Borbye

© 2008 Anders Borbye, used with permission- Title: Folia Folle (2008)

- Duration: 9'29"

- Recording date: August-September 2008 in the Frederikskirken, Aarhus, Denmark

- World première

- Gunge, Bo (1964- )

Duration: 1'01", 951 kB. (128kB/s, 44100Hz)

Fragment of A devil behind the mask,

performance by Anders Borbye

© 2008 Anders Borbye, used with permission- Title: A Devil Behind the Mask (2008)

- Duration: 8'56"

- Recording date: August-September 2008 in the Frederikskirken, Aarhus, Denmark

- World première

- Izarra, Adina (1959- )

- Title: Folías de España, sobre las Folías de Marina Marais de 1701 (1995)

- Duration: Introducción 0'38" Rápido 1'10" Muy rápido 1'25" Rápido, misterioso 2'19" Veloz 2'08" Lenta 5'08" Ansiosa, muy rápida 2'06" Final 2'02"

- Recording date: August-September 2008 in the Frederikskirken, Aarhus, Denmark

- Johanson, Bryan (1951- )

- Title: La Folia Folio (1995)

- Duration: 10'44"

- Recording date: August-September 2008 in the Frederikskirken, Aarhus, Denmark

- Malipiero, Riccardo (1914-2003)

- Title: Aria Variata, su la Follia (1979)

- Duration: 9'16"

- Recording date: August-September 2008 in the Frederikskirken, Aarhus, Denmark

'Espana en la Musica Europea de los Siglos XV al XVIII'

Genoveva Galvez

|

released 1977

total duration 42'45"

A recording centered aropund the theme of Spain in the title. No coincidence that three Folias were included.

Genoveva Galvez wrote about the Folia-theme in general::

La «Folía» es una danza portuguesa, cuyo origen

se remonta a tiempos muy antiguos. Ya Pedro 1,

al Justiciero, de Castilla, en el 1350, gustaba de

bailarla, A partir de 1500 se leen alusiones frecuentes

a esta danza en tratadistas de música

como Salinas, en literatos (Gil Vicente, Cervantes

.. . ), encontrándose, por otro lado, gra'n cantidad

de ejemplós musicales de ella en vihuelistas

y cancioneros. A principios del siglo XVII,

se pone de moda en toda Europa, con el nombre

de «Folía de España» ; casi todos los compositores

escribieron sobre este tema, baste decir

que, en tiempos más modernos, hasta Liszt y

Rachmaninoff han utilizado el tema de la «Folía»

en sus composiciones.

Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725), padre de Domenico,

el autor de tantas bellas sonatas para

e,1 clave, había trabajado con el gran Girolamo

Frescobaldi en Roma; de él aprendería la técnica

de la Variación, o «Partite», en la acepción italiana

más antigua de esta palabra. Existe, según

Willy Apel, un vínculo de unión entre Cabezón

y Frescobaldi a través de la escuela de tecla de

Nápoles, y de la que son exponentes magníficos

un Antonio Valente y otros compositores. La

«Folía», primitivamente danza, se , convierte en

tema básico de composición, y se presenta como

complejo armónico-melódico en el que están implicadas

las cuatro voces polifónicas (según el

mUSicólogo Miguel Quero!), pero cuya parte más

característica se sitúa en el bajo. Este bajo de

«Folía», se repite invariablemente a lo largo de

la obra como un bajo «ostinato». La «Folía» de

A. Scarlatti, de gran empeño virtuosístico, forma

parte integrante de una de sus «Toccatas».

Bernardo Pasquini (1637-1710) figura entre los

más insignes compositores italianos de tecla del

siglo XVII. En sus «Sonate per Gravicembalo»,

que incluyen toda clase de obras, desde «Toccatas

» o «Tastatas» a «Ricercares» y Variaciones,

muestra su fácil invención melódica, así como

una escritura a menudo influenciada por la música

violinística de la época. Su amor a la melodía,

a la suave cantabilidad italiana, influirá en

Handel, que trabajÓ con él en Italia.

Las «Folías de España», de C. Ph. E. Bach (1714-

1788) es una de las más cumpliélas obras escritas

con este tema. Sus diferentes variaciones

presentan fuertes contrastes. En 1759, C. Ph. E.

escribió en su «Vers"llch» o «Tratado sobre el verdadero

modo de tañer el clave» : ... - La música

ya no busca solo un placer de los oídos, 'sino

un desahogo de los más diversos sentimientos

del corazón». Dentro de esta nueva corriente estética,

de carácter subjetivo y personalista (que

en literatura recibe el nombre de «Sturm und

Drang») se sitúa su música para tecla; es, por

así decir, un anticipo del Romanticismo.

- Bach, Carl

Philippe Emanuel (1714-1788)

Folie d'Espagne performed Genoveva Galvez

Duration: 8'48" direct link to YouTube

© 1977 by Genoveva Galvez- Title: 12 Variations auf die Folie d'Espagne (1778)

- Performer: James Bonn (Dulcken fortepiano)

- Duration: 8'48"

- Recording date: not mentioned in the documention

- Pasquini, Bernardo (1637-1710)

Partite di Follia by Genoveva Galvez

Duration: 5'00" direct link to YouTube

© 1977 by Genoveva Galvez- Title: Partite di Follia (c.1697)

- Performer: James Bonn (Flemish harpsichord)

- Duration: 5'00"

- Recording date: not mentioned in the documention

- Scarlatti,

Alessandro (1660-1725)

Partite sull'Aria della Follia by JGenoveva Galvez

Duration: 19'05" direct link to YouTube

© Genoveva Galvez- Title: Partite sull'Aria della Follia

- Performer: Genoveva Galvez

- Duration: 7'05"

- Recording date: not mentioned in the documentation

Luigi Attademo

|

released 2001

total duration 59'35"

This compact disc was released by the Italian guitar magazine Guitart as the attachment of their quarterly issue. Unfortunately it is not yet distributed in the music shops outside Italy but only available through the magazine (guitart@guitart.it). However it is a great disc and worth attendance. First of all there are not that many recordings exclusively devoted to the Folia-theme and related music. The choice of repertoire is even more interesting because the Folia-variations of Angelo Gilardino, which are rather famous but hardly recorded because the high demands it requires of the guitar player, are the gravity center of this release. And it may be said, that piece is superbly played with flair and smootly, as expected by this gifted guitar player who attended seminars and masterclasses with Angelo Gilardino, so i guess the composer will be pleased with this performance.

Very helpful is the fact that all variations of the disc are indexed (47 tracks in total) so it is easy to skip to a particular variation or to make an analyse of pieces more easy. Even the Tiento by Maurice Ohana, which i personally consider as a non-folia (despite references in literature) because of its very remote association, sounds as a natural folia-conclusion in this context.

Although i am no connoisseur of guitar music, i like the natural tempi of the music. Lots of guitar players can't stand the temptation to play pieces as fast as possible which makes it a tour-de-force almost like a circus-act, but fortunately here the folias all sound in their right pace, at least the way i feel it. Further on the low basses sound cristal clear without overriding the treble-notes. But better judge for yourself because Luigi Attademo has put some samples in mp3-format (160 kbs) at his website http://www.luigiattademo.it/.

Luigi Attademo wrote for the slipcase (translation by Maya Bodo):

Nowadays the word insanity brings with it a meaning

which doesn’t leave any room to doubt, even though there may be several

meanings concealed in it. Between the two opposite poles of insanity

conceived as a disease, and insanity conceived as enthusiasm, each

artist is constantly looking for their particular characteristic, and

secret hiding places. The Iberian theme -the Folias - (a fast moving

dance) doesn’t have much to do with all this.

Such a path has its origin in Sanz, and ends up with the enigmatic

Ohana, touching pieces which are divided by different styles and

poetics, and it finally finds its center in Angelo Gilardino’s

Variazioni sulla Follia. It is not only by chance that they have been

conceived by their author as studies of Francisco Goya. Every time a

guitarist is looking into the guitar sound to be able to find the

meaning of human perceptions, and a way to give them back to their

audience, there is a reference to that particular poetic path.

Angelo Gilardino’s work rides Follía through hallucination. It

is only through hallucination that the world can be revealed in its

true sense. Without giving up the traditional way of composing with its

counterpoint, its interrupted and repeated themes, and its opposite

dynamics, Gilardino works out Follía again, and dives into it,

as an ancient alchemist, to develop diverse and unknown sounds. This

process transforms Follía into something that does not belong to

the author, into something that can be, at the same time, both

alienated and alienator. It is impossible to accomplish completely such

a kind of alchemistic process, and this is the reason why it ends up

with the quotation of Sor, another great guitarist who has chosen to

render and preserve the deepness and the torture of his thoughts by

means of a specific sound.

As far as this direction is concerned, Giuliani and Sor might seem

completely alien, yet their solidity is tinged with sadness which

marches side by side, for instance, with the fandango lively and

rhythmic reminiscence, which underlines the Iberian origin of the main

theme.

Gaspar Sanz compositions sound distant and almost impossible to listen

to, to our twentieth century ears. On the other side, the Tiento of

Maurice Ohana breaks through the Follía theme, and completely

tears it apart, enriching it with the mutation of a non-guitarist

composer.

Ponce is another non-guitarist composer connected to Andrés

Segovia’s figure, whose compositions are of great relevance. He is

surrounded by a traditional musical language, and this makes harmony

the real core of his expression. He makes the effort to compose a

monumental work, that is inspired by piano compositions, and that ends

- not by chance - with a fugue. He re-composes the theme again and

again in several different ways, broadening its shape. The result of

this process is a synthesis of his musical know how melded with some

kind of poetry of Segovian origin, which can be considered a milestone

in the way guitar sound has been conceived.

Preparing a collection containing these cycles of change can carry two

main purposes: walking through guitar history in a

linear way, showing at the same time that the artistic expression we

are looking for can appear in different ways, each one of them under

constant mutation, and both true and false at the same time. This can

appear alien to our perception, nevertheless it is part of that divine

madness which is the only component that can make the modern bard

strong enough to bear the impact with lack of meaning, which can be

considered the cause and the consequence of our insanity.

- Gilardino,

Angelo (1941- )

- Title: Variazioni sulla Follía (Studi da F. Goya) (1989)

- Duration: 1 Lento e pensoso 1'13", 2 Risoluto, ma non troppo mosso 0'59", 3 Andantino scorrevole e sommesso 0'59", 4 Allegro non troppo, ma assai energico 0'53", 5 Andantino appena mosso 1'56", 6 Allegretto 0'51", 7 Andante piuttosto lento 1'22", 8 Agitato 1'00" 9 Non troppo lento, con forte scansione 2'25", 10 Rapido e lieve 1'15", 11 Mosso, legato 1'22" 12 Liberamente, come preludiando F. Sor: Les Folies d'Espagne: Thème 1'21"

- Recording date: March 25 and 29 2001 at Quality Audio, Vercelli, Italy

- Guitar by Carlo Raspagni, 1996

- Giuliani,

Mauro (1781-1829)

- Title: Variazioni sul tema della Follia di Spagna op.45 (1814)

- Duration: 1 Tema: Andantino 0'45", 2 Variazione I 0'29", 3 Variazione II 0'22" 4 Variazione III 0'57", 5 Variazione IV 0'23", 6 Variazione V: un poco più adagio, Variazione VI 2'50"

- Recording date: March 25 and 29 2001 at Quality Audio, Vercelli, Italy

- Guitar by Carlo Raspagni, 1996

- Ohana, Maurice

(1914-1995)

- Title: Tiento (year of publication unknown)

- Duration: 4'54"

- Recording date: March 25 and 29 2001 at Quality Audio, Vercelli, Italy

- Guitar by Carlo Raspagni, 1996

- Ponce,

Manuel M. (1882-1948)

- Title: Variations sur 'Folia de España' et Fugue (1930)

- Duration: 25'35" All variations indexed

- You can listen to a fragment (opening) of the concluding fuga in MP3 (160 kb/s) at the website of Luigi Attademo http://www.luigiattademo.it/

- Recording date: March 25 and 29 2001 at Quality Audio, Vercelli, Italy

- Guitar by Carlo Raspagni, 1996

- Sanz, Caspar

(c.1640-c.1710)

- Title: Folías; (1674)

- Duration: 2'15"

- You can listen to the complete composition in MP3 (2,58 Mb) at the website of Luigi Attademo http://www.luigiattademo.it/

- Recording date: March 25 and 29 2001 at Quality Audio, Vercelli, Italy

- Guitar by Carlo Raspagni, 1996

- Sor, Fernando

(1778-1839)

- Title: Les Folies d'Espagne Variées e un Minuet op. 15a (c.1815)

- Duration: 1.re Variation 0'27", 2.me Variation 1'00", 3.me Variation 0'29", 4.me Variation 0'45", Menuet: Andante 2'00"

- Recording date: March 25 and 29 2001 at Quality Audio, Vercelli, Italy

- You can listen to the first variation in MP3 (542 kb) at the website of Luigi Attademo http://www.luigiattademo.it/

- Guitar by Carlo Raspagni, 1996

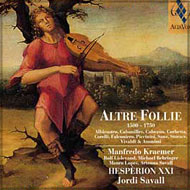

Hespèrion XXI conducted by Jordi Savall and other musicians

|

released September 2005

total duration 77'22"

Hesperion XXI plays Altre Follie (complete)

|

Chronologically, the timeline is respected much more with 'Altre Follie' to show the development of the Folia-styles as well as the diversity of instruments.

Once more there is no distinction made between the so called early or later Folias. There are some nice early Folias included like the ones by Cabanilles (hardly recorded), Cabezón, Corbetta, Piccinini and Storace.

The traditional instrumentation for the pieces is sometimes avoided and so some arrangements are surprizingly refreshing while others murder the soul of complete compositions. An example of the first category is the use of the 'arpa triple' as part of the b.c. in Faronell's Division which gives a charming and sparkling sound to the piece.

However I fail to see the purpose the way the Falconiero (Falconieri) is treated. Such a beautiful piece with three clear different voices tumbling over each other until they meet in unison at the very end (Falconieri gave the title the addition 'a 3' with good reason). Hespèrion XXI brings in 6 instruments and with 2 voices played by the same instruments (violin) and a b.c. without any unity (sometimes the theorbo disappears and in the opposite channel the harpsichord takes over). The result is a symphonic receptacle without any notion for the three interacting voices.

Peculiar is the way the harpsichord is recorded. Are the microphones deliberately positioned at a distance? The effect is that it seems that the harpsichord is not one of the pillars in the music. Especially when the instrument is put only in the right channel of the panorama (Falconiero) instead of a basso continuo that should be in the middle of the spectrum with the firm sound close at hand.

Let's not overestimate these minor irritations because most things are a treat. Extremely nice is the way Lislevand has engineered 'his' Folias taking different lines from the compositions of Corbetta and Sanz, to assemble the material into a 'new' piece with a familiar sound. Highlight of the disc I consider the composition by Albicastro. The only recorded version I know is of a magical spell recorded by Ensemble 415 and this version shows the same beauty and melancholy and as a bonus added a cheerful variation halfway the piece (written in the original score?) without breaking the magic reflection of the soul of the music.

The documentation of the disc is as always extremely nice with good texts in six languages and lots of photos.

In 2005 Rui Vieira Nery (University of Évora, Portugal) wrote for the slipcase (just quoting the text in regard to the later Folia):

In the seventeenth century several influential Italian composers

left us sets of Folia variations: the lutenist Alessandro Piccinini (1566-1638)

in his Intavolatura di Liuto (Bologna, 1623), for chitarrone; yet another lutenist,

Andrea Falconieri (1585/6-1656), in his Il Primo Libro di Canzone (Naples, 1650)

for two violins and continuo; the organist Bernardo Storace in his Selva di

Varie compositioni (Venice., 1664), for keyboard; the guitarist Francesco Corbetta

(d.1681), in his La Guitarre Royale (Paris, 1671), for his own instrument.

Corbetta seems to be one of the first authors to superimpose to the traditional

bass of the Folia the characteristic treble melody in triple meter, with a dotted

second beat in each measure, that was to become associated with the genre from

the late seventeenth century on. In fact, Gaspar Sanz' 1674 version was basically

an adaptation of Corbetta's setting., which the Spanish master must have acquired

shortly after its publication in Paris. This same combination of upper melody

and harmonic bass circulated widely all over Europe and became a favourite object

for variations, first in France itself, where it was employed by Lully and Marais,

then in Germany, the Netherlands and England, where the publisher John Playford

(16231687/88) included a set of Folia variations for the violin in his instrumental

collection The Division Viol (London, 1685), under the title "Faronell's

Division", which seems to have been traditionally associated with the Folia

in that country. At the same time, the most commercially successful French and

Italian dance treatises of the period, such as those by Feuillet (1700) and

by Lambranzi (1716), spread the tune and the basic steps of this "Folie

d'Espagne" through all the European market.

With the development of the virtuosic repertoire for the violin at the turn

of the century it was only natural that the Folia should be included in it.

In 1700 the great Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713) used it as the basis for a series of exceedingly virtuosic variations with which

he concluded his most influential collection of solo sonatas for violin and continuo, the famous Op. 5, the contents

of which are known to have circulated in manuscript for more than a decade prior to this

printing. In 1704 one of the most representative composers of violin music of the German and Dutch

school, Henricus Albicastro, an artistic pseudonym of Johann Heinrich von Weissenburg

(ca. 1660 -ca. 1730), published a sonata "La Follia", which displays a clear Corellian influence

in its virtuosic writing. And it was not by accident that a year later, in 1705, the young Antonio Vivaldi

(1678-1741) also chose to conclude a decisive publication in which he placed the highest hopes

for the future of his artistic career, his Op. 1 collection of trio-sonatas, with yet another magnificent

set of Folia variations.

The old Portuguese peasant dance had come a long way. To the very end of the

Baroque period it would remain one of the strongest unifying traits of European instrumental music,

a well-known basis upon which musicians from all nations could improvise together without

any barrier of language or of musical tradition, and a successful source of inspiration for any composer who wished

to impress the European music community at large with his skills. On the contrary, Classicism,

in its search for larger formal structures in music, was not so interested in ostinato basses,

but still the Folia was yet to be occasionally rediscovered by the Romantics, at the hands

of such masters as Liszt or Rachmaninov.

- Albicastro

(von Blankenburg or Weissenburg), Henrico (1661-unknown)

Hesperion XXI plays Albicastro

Duration: 11'41" direct link to YouTube

© 2005 by Alia Vox- Title: Sonata "La Follia"

- Performers: Kraemer, Manfredo (violin), Ruiz, Mercedes (violoncelle), Behringer, Michael (harpsichord)

- Duration: 11'41"

- Recording date: February 28-March 3 and June 6-9, 2005 in the Collégiale of the Château de Cardona, Catalogne

- Corelli,

Arcangelo (1653-1713)

- Title: Follia (1700)

- Performers: Manfredo Kraemer (violin), Balazs Mate (violoncello), Xavier Díaz-Latorre (guitar), Carlos García-Bernalt (harpsichord)

- Duration: 11'00"

- Recording date: February 28-March 3 and June 6-9, 2005 in the Collégiale of the Château de Cardona, Catalogne

- Falconiero (Falconieri), Andrea (c.1575-c.1661)

Hesperion XXI plays Falconieri

Duration: 4'29" direct link to YouTube

© 2005 by Alia Vox- Title: Folias (a 3) echa para mi Señora Doña Tarolilla de Carallenos

- Performers: Manfredo Kraemer (violin), Mauro Lopes (violin), Balazs Mate (violoncello), Xavier Puertas (violone), Xavier Díaz-Latorre (theorbo), Carlos García-Bernalt (harpsichord)

- Duration: 4'32"

- Recording date: February 28-March 3 and June 6-9, 2005 in the Collégiale of the Château de Cardona, Catalogne

- Farinel(li), Michel (c.1649-unknown)

- Title: John Playford: Faronell's Division (1684)

- Performers: Manfredo Kraemer (violin), Jordi Savall (basse de viole), Arianna Savall (arpa triple)

- Duration: 5'07"

- Recording date: February 28-March 3 and June 6-9, 2005 in the Collégiale of the Château de Cardona, Catalogne

- Sanz, Caspar (& Francesco Corbetta) (1640-1710)

- Title: Folias (1674)

- Performer: Rolf Lislevand (guitar)

- Duration: 3'14"

- Recording date: February 28-March 3 and June 6-9, 2005 in the Collégiale of the Château de Cardona, Catalogne

- Vivaldi, Antonio (1678-1741)

- Title: Sonata "La Follia" Op.1 n.12 RV63 (1705)

- Performers: Manfredo Kraemer (violin), Mauro Lopes (violin), Balazs Mate (violoncello), Xavier Puertas (violone), Xavier Díaz-Latorre (guitar), Carlos García-Bernalt (harpsichord)

- Duration: 9'44"

- Recording date: February 28-March 3 and June 6-9, 2005 in the Collégiale of the Château de Cardona, Catalogne

Ruggero Laganà joined by

M. Pennicchi (soprano), M. Lonardi (archlute & vihuela), P. Beschi (violoncello), F.C. Quatu (sopranistu), T. Bracci (bass)

|

released April 2005

total duration 148'39"

This extraordinary double compact disc set was released by the Italian magazine Amadeus (15th year No. 2, April 2005) as the attachment of their issue which was completely devoted to the la Folia-theme in music edited by Pinuccia Carrer, professor of musical history at the conservatory of Milan.

The only disadvantage is that all documentation is in the Italian language, but sources are well documented and every detail both of the music as the magazine is taken care of with precision.

The discs contain lots of 'later' Folias, but also some early Folias, famous in literature but hardly recorded like the one written by Giovanni Stefani and the beautiful piece for vihuela by Diego Pisador. The best thing about the music, which is mainly for keyboard (harpsichord and fortepiano) is that almost every piece of music is indexed (visible in the display of the cd-player) and even the number of bars is indicated in the slipcase. This is an extra dimension which invites to examine the pieces even more closely.

Besides these Folias there is a selection of music included like the famous fandango by Antonio Soler, the Capriccio op. 34 no 1 by Muzio Clementi and the Fantasie in G min op. 77 by Beethoven which are out of the ordinary in their own field.

The only thing I cannot understand is why the Prelude and Sarabande (3rd Suite in d minor) of Jean-Henry d'Anglebert is included and his most famous Folies d'Espagne from the same bundle is left out of the selection. I guess it will be all explained in the detailed documentation, but unfortunately I cannot read any Italian and that is my only frustration of this fantastic release.

- Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel

Maestro Laganà plays 12 Variations auf die Folie d'Espagne (Wotq 118/9 H. 263)

Duration: 8'04" direct link to YouTube

© 2005 by Ruggero Laganà- Title: 12 Variations auf die Folie d'Espagne (Wotq 118/9 H. 263)

- Duration: 8'04"

- Recording date: August 18-19 and November 15-19, 2004 in Chiesa di S. Maria Incoronata, Martinengo (Bg), Italy

- All variations nicely indexed

- Cramer, Johann Baptist

- Title: Follia di Spagna

- Duration: 3'53" (duration of Divertimento X: 18'49")

- Recording date: August 18-19 and November 15-19, 2004 in Chiesa di S. Maria Incoronata, Martinengo (Bg), Italy

- All variations nicely indexed

- Händel, Georg Friedrich

Maestro Laganà plays Sarabande by Händel

Duration: 4'43" direct link to YouTube

© 2005 by Ruggero Laganà- Title: Sarabanda e variazioni dalla Suite in re minore per clavicembalo

- Duration: 4'43"

- Recording date: August 18-19 and November 15-19, 2004 in Chiesa di S. Maria Incoronata, Martinengo (Bg), Italy

- All variations nicely indexed

- Martín Y Coll, Antonio

Theme and 3 variations.

Source: in Huerto ameno de varias flores de música recogidas de muchos organistas por Fray Antonio Martín 1708, Madrid, Bibliotheca Nacional, Ms 1359, pp 593-595.- Title: Folias (1708, tema di Follia di 7 battute ripetute e variate quattro volte, con diminuzioni)

- Duration: 1'42"

- Recording date: August 18-19 and November 15-19, 2004 in Chiesa di S. Maria Incoronata, Martinengo (Bg), Italy

- Martín Y Coll, Antonio

Theme and 8 variations

Source: in Huerto ameno de varias flores de música recogidas de muchos organistas por Fray Antonio Martín 1709, Madrid, Bibliotheca Nacional, Ms 1360, ff. 215v-217v- Title: Otras Folias per clavicembalo (1709)

- Duration: 2'17"

- Recording date: August 18-19 and November 15-19, 2004 in Chiesa di S. Maria Incoronata, Martinengo (Bg), Italy

- Three parts of variations nicely indexed

- Martín Y Coll, Antonio

Theme and 7 variations

Source: in Pensil deleitoso de suabes flores de música recognidas de varios organistas por F. Antonio Martín 1707, ff. 68r-69r.- Title: Tonos de Palacio - Folias (1707, Tema di Follia di 8 battute ripetute con otto variazioni)

- Duration: 2'22"

- Recording date: August 18-19 and November 15-19, 2004 in Chiesa di S. Maria Incoronata, Martinengo (Bg), Italy

- Pasquini, Bernardo

Source: Staatsbibliothek Berlin Preuäischer Kulturbesitz, Landsberg 215 - Parte IIIMaestro Laganà plays Partite diversi sopra Follia

Duration: 7'24" direct link to YouTube

© 2005 by Ruggero Laganà- Title: Partite diversi sopra Follia (ca. 1697)

- Duration: 7'24"

- Recording date: August 18-19 and November 15-19, 2004 in Chiesa di S. Maria Incoronata, Martinengo (Bg), Italy

- All variations nicely indexed

- Scarlatti, Alessandro

Source: GB-Lbl, una più tarda versione in US-NH, in Toccate per cemalo, a cura di J.S. Shedlock, London 1908- Title: Variazioni sopra la Follia di Spagna (1723)

- Duration: 8'24"

- Recording date: August 18-19 and November 15-19, 2004 in Chiesa di S. Maria Incoronata, Martinengo (Bg), Italy

- All variations nicely indexed

Ensemble Oni Wytars

|

released 2013

total duration 61'51"

In 2011 it was exaclty 500 years ago that "In Praise of Folly" by Erasmus of Rotterdam was published. It was a moment of extra focus for the essay. Since Folly (literally meaning "madness") can be translated to Folia or Follia in Italian it can easily be associated with the famous archtype La Folia in music. The occasion for musicians to consider to do something with this achtype in music in connection to Erasmus.

Jordi Savall released in 2012 a pacxkage of 6 compact discs and more than 500 pages of text by Erasmus in several languages where the praise of Folly was the central theme. Most tracks however were recorded before and only one later original Folía was included by the harpist Andrew Lawrence King.

This disc by Ensemble Oni Wytars is considering the musical archtype La Folia far more interesting. Besides lots of early Folías like the well-known pieces by Ortiz, an arragement of Piccini for keyboard (originally chitarrone) and the hauting tune by Baldano (also recorded by La Cetra d'Orfeo), six later folías were included. The Falconieri is a rather standard version but the Folies d'Espagne by Chediville was not yet recorded as far as I know. The remaining folías are very original improvisations by masters on their instruments (Harrison and Pessi), a Scandinavian setting for an Italian Folia by Corelli (Ambrosini) and a full arragement for voices based upon Vivaldi's Follia (Sontata "La Follia"). The only disadvantage is that the documentation about the sources, although the texts are in three languagues, is rather poorly. They rather like to play the tunes than doing research and justify their choices. The folly for every librarian looking for the original manuscripts, so be it.

The Members of the Ensemble Oni Wytars are:

Belinda Sykes, voice Gabriella Aiello, voice Su Ehlers, voice Peter Rabanser voice, ceccola polifonica, baroque guitar lan Hariison, bagpipes, cornet, voice

Riccardo Delfino, hurdy-gurdy, harp, bagpipes, voice Jule Bauer, tenor nyckelharpa, voice Katharina Dustmann, percussion Carlo Rizzo, Tamburello, tambourin polytimbral Michael Posch, recorders Giovanna Pessi, harp Jane Achtmann, Viola da gamba, Michael Behringer, organ Marco Ambrosini, nyckelharpa, jew's harp and director

An impression of the recording session October 2011

|

Marco Ambrosini wrote for the slipcase (in a translation by Ian Harrison & Peter Rabanser):

500 years ago saw the publication of Erasmus of Rotterdam's famous book The Praise of Folly. In this essay Erasmus praised Folly in a humorous and virtuoso way, depicting her

as a benevolent goddess, who has inspired the human race since time immemorial, ever protecting

us from the bitter seriousness of life.

There is no musical genre that comes closer to this world view, and expresses it more

accurately, than the Follia, or Folia, a form of composition which has been a major factor of western music history from the 15th century to the present day. Hundreds of composers have

dared to approach - and relished - the Follia; there is hardly a famous musician who has not

put his or her signature to at least one such composition. It is a constant temptation, an

addiction; each new variation should - in the truest sense of the word - be crazier than the previous one. The list of Follia compositions, which extends from the Renaissance to contemporary

pop and rock music is indeed long and impressive.

These are many good reasons for the ensemble Oni Wytars to continue this unbroken tradition, to adorn it with new facets and sounds, to look at it afresh, and to present to modern audiences this constantly self-reinventing world of the Follia. An impressive selection of exotic and ancient instruments such as baroque hurdy-gurdy, nyckelharpa, chitarra, battente, doublé harp, polyphonic bagpipes, cornet, recorder, organ, viola da gamba and various types of percussions meet with rather unconventional vocals expressing sometimes grotesque and foolish texts from the Mediterranean Baroque. Follias by anonymous masters mingle with folk songs and then lose themselves in the well-known instrumental works by Vivaldi and Corelli; boundaries melt away until the composers just step aside and listen with a smile. The Follia emancipates itself from the shackles of written texts and the standard repertoire, it recreates itself and bursts, along with the song, into a real musical firework full of highly virtuoso improvisation, joy, imagination and of course ... Folly!

- Ambrozini, Marco (1964- )

- Title:Follia d'Arcangelo (2011)

- Duration: 0'37"

- Recording date: October 1-3, 2011 in Kurtheater, Bad Kissingen, Germany

- Chédéville, Nicolas (1705-1782)

- Title: Les Folies d'Espagne (c. 1750)

- Duration: 2'44"

- Recording date: October 1-3, 2011 in Kurtheater, Bad Kissingen, Germany

- Ensemble Oni Wytars

(Ensemble) based upon Vivaldi

- Title: Sonata "La Follia" (2011)

- Duration: 10'01"

- Recording date: October 1-3, 2011 in Kurtheater, Bad Kissingen, Germany

- Falconieri, Andrea

(1585-1656)

- Title: Follia (1650)

- Duration: 2'08"

- Recording date: October 1-3, 2011 in Kurtheater, Bad

- Harrison, Ian

(? - )

- Title: Folia Gaitata (2011)

- Duration: 2'08"

- Recording date: October 1-3, 2011 in Kurtheater, Bad Kissingen, Germany

- Pessi, Giovanna (?- )

- Title: Follia dell'Arpa (2011)

- Duration: 1'20"

- Recording date: October 1-3, 2011 in Kurtheater, Bad Kissingen, Germany

Yves Storms

|

released 1983

total duration 45'01"

In this recording are three massive sets of variations included on the 'later'folia-theme and one set of early Folias by Barttolotti.

Peter Pieters wrote for the inlay of this vinyl recording:

In Baroque times, no melody or chord

schema was more often used in

variations than the Folly from Spain.

Incontestably, Corelli's «La Folia» is the

most famous, but even ].S. Bach used the

theme' in his «Peasant Cantata».

Originally, the Folly was a wild dance, in which men in carnival costume often

~eached a state of hysterical trance. The Church did not approve and as a result

the Folly was gradually transformed into

the slow, solemn melody we know today

The Folly was extremely popular among baroque guitar players, to the

point that Robert de Visee - almost alone in not publishing one - felt it

necessary to write in his introduction:

«Neither will one find here the Spanish Folly. So many of these are now to be

heard, that I could only repeat the follie of others».

There is not the space here to list all the Follies written for the Baroque

Guitar, but the three collected on this record are among the most beautiful:

that of the Spaniard F. Gereau, the Brussels-born F. Le Cocq and the ltalian

A.M.B. whose works have been neglect to this day.

In later times as well, guitar players have shown their partiality for the Spanish Folly and the two greatest guitar composers of the 19th Century, Fernando Sor and M. Giuliani, wrote variations on

these themes. In our own times the Mexican Manuel Ponce, who wrote principally for the guitar,